[![]() Preliminary Ethnographic

Research on the Bakoya in Gabon / Soengas, Beatrizi / KURENAI Japan]

Preliminary Ethnographic

Research on the Bakoya in Gabon / Soengas, Beatrizi / KURENAI Japan]

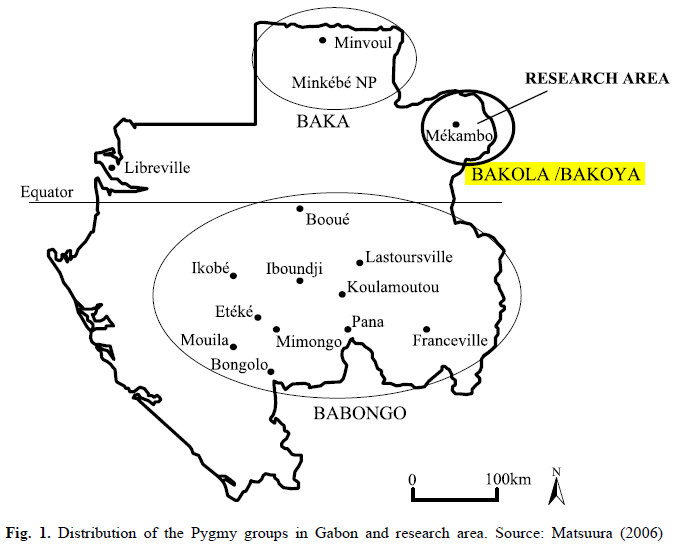

The Bakoya are pygmies, earlier known as Négrilles or Babinga, who inhabitant the rainforest between Cameroon and the Great Lake region of the Congo Basin in Central Africa. Since the 1930s, the Bakoya, in particular, have settled in Gabon in the Ogooue-Ivindo Province, in the northeastern region of the country.

Bakoya pygmies can be found in Republic of Congo and border with Gabon.

Pygmies living in the Imbong village are specifically known as Bakoya. They are situated in the Ogooue-Ivindo Province, which is one of the nine provinces of Gabon. They are settled along the Mékambo to Mazingo (Canton Djoua) road and (Canton Djoua), and from Mékambo to Ekata (Canton Loué) road in the Zadié Department.

The Bakoya do not speak an original language: even if it had existed in the

past, they have lost it. They speak the Koya, a form of Ngom, a Bantu language

corresponding to B22B in Guthrie (1971) classifi cation. Koya is a close dialect

of Ngom, with little lexical and phonological differences. (Medjo-Mve, 2004).

The Bakoya also speak French as well as other Bantu languages (Kwele, Kota)

spoken by their neighbors.

The Bakoya and their non-Pygmies neighbors share some social and organizational

features, and participate together in different ceremonies that punctuate the

life of the village.

Like their non-Pygmy neighbors, the Bakoya have a so-called Hawaiian type

classifi catory kinship terminology. For an Ego, the men of his generation are

considered to be his “brothers” and the women his “sisters.” Similarly, men of

the generation of one’s father are considered as his “fathers,” and the women of

such generation considered as one’s “mothers.” The Bakoya are exogamous, and

they cannot marry a person of the same clan. The lineage system is patrilineal

and residence is virilocal, although some men leave their village to settle in the village of his wife for an indefi nite period. Similarly, when his parents-in-law

beckon him to work in their farms, he may leave his village to work with them.

Once a part of bridewealth has been paid by the man to the family of his future

wife, the young couple move to the house built by the husband in the village of

his parents. The bridewealth today consists of a certain sum of money, chickens,

machetes, etc., and payment can be deferred in time.

Most Bakoya have names from Ngom clans, for example, Sayuka or Samwadi,

and sometimes from another non-Pygmy group, for example, Sabololo (Kota).

The non-Pygmies gave their own clan names to the Bakoya families with whom

they have the closest relationships. Children, boys and girls alike, are members

of the father’s clan. In mixed couples where the father is non-Pygmy, the children

belong to their father’s clan.

The Bakoya make regular visits to their parents living in other villages, staying

up to several months with them. Visits are important to maintain contact and to

strengthen the relations between the members of a family. It is also the moment

to share gifts and news. Visits to other villages are also the opportunity to find

one’s partner, usually during summer holidays, funerals and other ceremonies.

Most circumcision ceremonies (Mungala) occur during summer. People sometimes

travel to distant villages to attend the circumcision of a family member. The

ceremony lasts three days with different stages, and provides the occasion for the

family and the entire village to celebrate together the courage of the young boys,

to share food and alcohol. It is indeed a diffi cult test that involves the honor of

the boy and his family. Originally, the Mungala was a non-Pygmy ceremony.

Non-Pygmies families observe the circumcision of the Bakoya boys, providing

support, money and goods. In return, because the Pygmies are considered to be

great singers, musicians, and dancers, no ceremony can take place without their

support.

Other important ceremonies still practiced by all communities are the mourning

ceremonies, called retrait de deuil and levée de terre. Minor ceremonies, such as

issembu, a feminine initiation, are either vanishing, or tend to be mingled with

Christian traditions. The “ceremony of the twins,” for example, is now sometimes

celebrated in the Christian way.

The Pygmies and non-Pygmies alike frequent the numerous Evangelical churches

(La Bonne Semence, L’Alliance Chrétienne and La Vie Profonde) that fl ourish in

both Imbong and Ekata villages. A lesser fraction of the Bakoya and non- Pygmies

frequent the Catholic church of Mékambo or Ekata. Very few have converted to

Islam, mostly those who worked with Haussa shopkeepers. The term, “Haussa,” encompasses all Muslim traders and shop owners from West-African countries,

such as Mauritania, Chad, Cameroon and Mali. All shops in Mékambo belong to

the Haussas.

However, Bakoya and non-Pygmies still hold a strong belief in wild spirits or

“genies” living in the forest, for example, Djundju, who cries and steals children

who wander in forest.

Pygmies are known for their egalitarian community and acephalous political

organization. When living in the forest, decisions were made by an assembly of

elders. During the colonial period, the French military asked them to choose a

chief for each village. In Imbong and Ekata, the Bakoya have their chief elected

by the inhabitants. For example, the Bakoya chief of Mangombe, a village

which forms part of the regroupement of Imbong, is elected by the inhabitants

of Mangombe. The chief of the regroupement is elected by all the people living in Imbong. However, the Koya chief does not make any decision before he

consults the elders of the village. When there is a problem in the village, people

have to speak fi rst with the village chief. If no solution can be found, the problem

is brought to the regroupment chief, then to the canton chief. If still no solution

has been found, the problem goes to the prefecture. The chief of the village

incarnates the administrative authority at the cell level and has diverse functions.

He ensures the application of the law, embodies the administrative police, looks

after the village health and signals the epidemics, participates with his population

in local development actions decided by the cantonal council, registers births and

deaths, and helps in the census-taking. At the national level, there is no Pygmy

representation in the Government nor in the Gabonese Parliament. However, non-profi t organizations, including the MINAPYGA (Mouvement des Minorités

Autochtones, Indigènes et Pygmées du Gabon) founded by a Bakoya, work to

bring awareness to the national and international level as to the Pygmy diffi culties,

and strive for more considerations to be given to these populations at the social

and political levels.

There are few data concerning the demography of the Bakoya in Gabon. In

1960, Cabrol counted 970 Bakoya (Cabrol, 1960), and in 2002, Leclerc and

Annaud (2002) reported 2,160 Bakoya living in Gabon. In both Imbong and Ekata

villages, the Bakoya are in signifi cant majority. The Bongom in Imbong Village are a very small community, while in Ekata, they accounted for

a third of the population, and formed the majority of the non-Pygmies.

As described above, the Bakoya and non-Pygmies have had long-established

relationships. Both communities are connected through alliances of social, political,

and emotional solidarity, creating lasting friendships and partnerships that transcend

ethnic boundaries (Rupp, 2003: 41). Some Bakoya and non-Pygmies still have

duties towards each other, in terms of providing food and services on the part of the Bakoya, and protection and care on the part of the non-Pygmies. The latter

describe this mutual assistance as a sort of “social security” system. Alliances

and friendships, collective ceremonies, and cooperative activities foster sentiments

of social solidarity (Rupp, 2003: 39). However, the Bakoya to this day are still

the subject of disparagement from non-Pygmies communities.

However, some Bakoya no longer feel subordinate to the other Bantu ethnic

groups. As the Bakoya now earn their own money and engage in the same activities,

the distinction among these groups tend to vanish. I will now describe the subsistence

and economic activities practiced by Bakoya Pygmies.

The forest surrounding the villages, from which the people extract the natural

resources needed for their subsistence, is a semi-caducifolius forest, with an

altitude between 490 and 525 m, interspersed with secondary forests near the

villages and swamp forests along the Zadié and the Djoua Rivers. Rivers and

backwaters form a network that the Bakoya use as pathways and fi shing spots.

Annual rainfall is between 1,600 and 2,000 mm. The frequency of the various

activities changes depending on the season. There are four seasons, two of low

rainfall around January and July, and two of heavy rain in October and around

April–May.

The Bakoya and their neighbors share the same space and the same resources,

even if sometimes, as in the case of agriculture, the places are referred to as

belonging to one ethnic group, as I will show below. Concerning the Bakoya

social organization of work, the Bakoya distinguish some activities such as hunting

mostly suitable for males, and some other activities suitable for females, such as

fi shing. This sexual division of labor is expressed more in terms of cooperation

between the sexes than by a rigorous dichotomy. A woman still can do what a

man does, if she wants to do so, and provided that she learns how to do it. The

only taboo is the prohibition for a woman to go hunting with her husband and

to pound cassava when she has her periods.

Since they settled, the Bakoya invested themselves more and more in agriculture,

to the detriment of some “traditional” activities that eventually disappeared.

However, there are variations in the subsistence activities carried out by the

Imbong and Ekata villagers. I compare below these two villages in terms of

hunting, fi shing, collecting, agriculture and trade.

Following the many internecine wars among the tribal groups of the region, the Bakoya, who were living on the banks of the Ogooué River migrated along with the non-pygmy group of Bongom to an upstream region of the Ivindo and Zadié Rivers. According to the oral traditions of the Bakoya, during their travel through the forests they accompanied the Bongom, a non-pygmie tribe. While the Bongom moved out of the forests and established themselves on the Mékambo-Mazingo Road by setting up the villages of Ego, Grand Itumbi, Ngunangu and Ibea, the Bakoya had stayed back in the forest to harvest their crops of u.panda (Panda oleosa) and did not move to the Mékambo-Mazingo Road immediately. At this time the French who had colonized Gabon also created better living facilities.

The Bakoya, Baka and Babongo are three minorities groups of Gabon who are known as the “Pygmies of Gabon” (said to be the first people to inhabit the forests of Gabon) and they form a very small minority of a few thousand people only. All of them have left behind their hunter-gatherer vocation to more "sedentary" modern way of life. Their skills of hunting game with “bow and poisoned arrows, game traps and harpoons” are however much more skillful than the majority population of the Bantu community in the country. But their lot is subject to humiliation at the hands of the Bantus. However, in recent years there is an effort to project their history as a matter of tourism interest and their culture has been brought forth in the form of exhibitions, lectures and discussions. One such initiative was taken in 2002 when an exhibition was organized to project the history of pygmies and their culture.

The government of Gabon recognized the Minorités Autochtones Pygmées au Gabon (MINAPYGA; the Indigenous Pygmy Minorities of Gabon) organization of Bokayo in 1997, which is one of three such indigenous organizations in the country; the other two recognized groups are the Edzendgui and the Association pour le Developpement de la Culture des Peuples Pygmees du Gabon.

Sources: