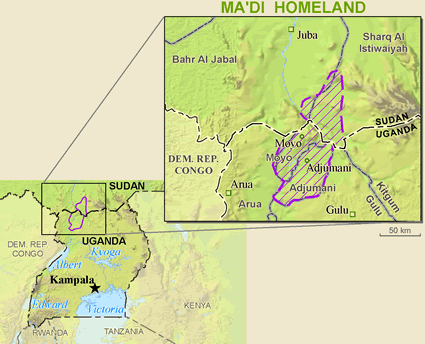

The Mà'dí people live in Pageri County in South Sudan, and the districts of Adjumani and Moyo in Uganda. From south to north, the area runs from Nimule, at the South Sudan-Uganda border, to Nyolo River where the Ma’di mingle with the Acholi, the Bari, and the Lolubo. From the east to west, it runs from Parajok/Magwi to Uganda across the River Nile. The Madi people inhabit the southwestern part of Torit district where the Nile River makes a sharp bend into Uganda. In Uganda, they are found in west Nile districts of Moyo and Adjumani. |

|

The porous nature of the borders between Sudan and Uganda has made the Madi move and settle freely on either sides of the border during the civil wars in the two countries.

The just concluded 22 year civil war sufficiently diminished the number of Madi in the Sudan and most of their villages are now occupied by displaced people from other parts of the South.

The Madi stalk the common borders with Uganda. They neighbour:

Madi territory is hilly and traversed by rivers and streams. The Madi are sedentary agrarian community. Their economy is based on subsistence agriculture, in which the main crops are sorghum, maize, cassava, groundnuts and tobacco. In the 1960s, the farming of tobacco was introduced as a cash crop but this was disrupted by war. The Madi rear small herds of cattle, goats and sheep as well as fowl.

Mythology and historyThe mystery of birth tends to puzzle the Madi, whose beliefs are based on reproduction and hence, their origin as a people. Rabanga is the supreme being responsible for creation. In addition to being a spirit, Rabanga was also regarded as the earth in the sense of ‘Mother Earth’. This was grounded in the logic that everything is born from the earth. According to one popular folk tale, the name Madi came as an answer to a question by a white man to a Madi man. When the first white person in the area asked the question 'who are you?', the bemused response was madi, i.e. a person. This was taken to be the name of the people, which came to be corrupted to the present. Another Ma'di narrative tries to account for the names of some of the Moru–Ma'di group members. When the progenitors of the Ma'di were pushed southwards, on reaching a strategic location they declared, Muro-Amadri, i.e., "Let's form a settle here". And so they formed a cluster to defend themselves. This group came to be known as the Moru. A group broke off in search of greener pastures in a more or less famished state, until they found an edible tree called lugba('desert dates' - ximenia aegyptiaca). After they ate some of the fruits, they took some with them. When the time came to refill their stomachs again, a woman who lost her harvest was heard enquiring about the lugba ri 'the desert dates'. This group came to be known as logbara but the Ma'di still call them lugban. The final group on reaching fertile grounds resolved and declared ma di 'here I am (finally)'. And these came to be known as the Ma'di. |

|

|

The speakers refer to themselves and are known as Madi. In standard orthography, this is Ma'di; the aprostrophe indicates that d is implosive. The speakers refer to their language as madi ti, literally meaning Ma'di mouth. Among themselves, Ma'di refer to each other as belonging to a suru ("clan" or "tribe"), which may further be broken down to pa, "the descendants of," which in some cases overlap with suru. While a Madi can only marry someone from outside their clan, they must normally marry within the group that shares the Madi language.

The social and political set-up of the Madi is closely interwoven with spirituality and this informs their attitudes and traditions. The society is organized in chiefdoms headed by a hereditary chief known as the Opi. The Opi exercised both political and religious powers.

The rain-makers, land chiefs – vudipi (who exercises an important influence over the land) and the chiefs are believed to retain similar powers even after their deaths. There was a hierarchy of spirits corresponding exactly to the hierarchy of authority as it existed in the society.

The birth of twins is considered an ill-omen among the Madi attributable to Rabanga. Twins were regarded as mysterious creatures and in fact the elder of the twins was named Ejaiya meaning ''take him to the bush'' and the younger Rabanga.

Rainmaking There are more than 45 rainmaking centres in the Madi country. With only two exceptions, rain could be made by the rainmaker by using a special set of stones which, were usually white in colour. The Madi believe that ‘rain stones’ come with rain from the sky and they are categorised as ‘male’ and ‘female’ stones. |

|

The chiefs and clan elders exercise judicial powers of settling cases. However, in cases where the suspect pleaded innocence to accusations of stealing or adultery, the witch doctor was consulted. The witch doctor would take a handful of spear grass and order the accuser and the accused to hold each end of the grass. The witch doctor would then cut the spear grass with an arrow. Whoever was guilty would fall sick and the truth would establish itself through the consequences.

The whole life of the Madi is centred on the belief that their ancestors survived after death as spirits known as ori. It is believed that the ori could intervene directly in human affairs. The Madi attribute every misfortune to the anger of a spirit and in the event of a misfortune or sickness, they would immediately consult an odzo or odzogo (witchdoctor) to find out which ancestor was behind the ordeal.

Sacrifices were then offered to the particular spirit in order to avert its malign influence on the living. The powerful families among the Madi bas were believed to have powerful ancestral spirits to help them. ''Babu-garee'' constitutes the whole paraphernalia of the spirits of the dead.

Ori – the spirits of the reincarnated ancestors

Before the coming of Christianity and Islam to Madi, the predominant religion of Madi people was all about the belief in, and the worship of ancestors who were believed to survive death in form of spirits known as ori. It was believed that the ori could intervene directly in human affairs. Thus the Madi attribute every misfortune to the anger of a spirit and in the event of a misfortune or sickness, they would immediately consult an odzo or odzogo (spirit-medium) to find out which ancestor was behind the ordeal. Sacrifices were then offered to the particular spirit in order to avert its malign influence on the living. The powerful families among the Madi were believed to have powerful ancestral spirits to help them however with conversion of majority of Madi people to Christianity, and some to Islam, Rubanga - the Christian God and the Allah of Islam, took the places and roles which once belonged to the ori.

Nonetheless, today in the age where most Madi people have converted to the foreign religions, still some believers in the traditional Madi religion try to build a bridge between Rubanga and Ori. Today some Madi people still keep miniature altars called Kidori, were sacrifices are offered to the ancestral spirits in both in good and bad times as a way to approach God. Often at harvest time, the first harvest must be offered to the spirits to thank them for successfully interceding to God on behalf of the living.

Spirituality and the Madi Deities

Besides the belief in ori, the Madi people also believe in creatures, which are not the spirits of the reincarnated ancestors, but they are deities in their own right. Some of these deities are sacred trees, hills, rivers, snakes, etc. For example, among the Moli clan, Jomboloko (a tortoise who is believed to be living in a hill around Moli Tokuru hill), is well known deity. Many stories have been told about Jomoloko. Some Moli people still believe in Jomboloko. In the pre-Christian age, it was common practice for a group of people believe in more than one deity. In that sense, some Madi people were polytheistic in their belief. However today, belief in those creatures diminished considerably.

Christianity

Christianity was first introduced to the Sudan, i.e. Nobatia (northern Sudan and part of Dongola), by a missionary sent by Byzantine empress Theodora in 540 AD. The second wave of Christianity to the Sudan came during the time of the European Colonialism. In 1892, the Belgian expediters took parts of southern Sudan that came to be named Lado Enclave (i.e. the western bank of Upper Nile region which is today the southeast Sudan and northwest Uganda). After the death of king Leopold II on 10 June 1910, the Lado Enclave, became the province of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, with its capital city at Rajaf. In 1912 the southern part of Lado Enclave become part of northern Uganda, which was also the British Colony. It was during that time the Madi people were divided into the Sudanese and Ugandan Madi. Christianity to the northern part of Lado Enclave was brought via Uganda at about the same time - as Colonialism always went hand in with Christianization.

The notion God and the Madi word for it Rubanga, have very recent history. They came with Christianity. For example, in the Roman Cathotic Catechesis in Madi language, when asked Rubanga ido oluka adu nga (How old is God), we're expected to answer Rubanga ido oluka ku (God has no beginning). And when asked Adi obi nyi ni oba nyi vu dri ni (who has created you and put you on the Earth), you are expected to answer Rubanga obi mani obama vu dri ni (God has created me and put me on Earth). And we are also asked to believe ta Rubanga abi le ati ri anjeli (the first things God created were angels).

Moving away from the Christian paradigm, if you are to go back in time, you reach beroniga. Before that there was nothing; the notions like time and space are void of meaning and content. Thus vu(space-time) came along with beronigo and all events and creation came after beroniga.

Now without the context of Christianity, in Madi cosmogony there is no say Rubanga obi vu ni. That cannot be the case since Rubanga came to Madi with Christianity, while vu (space-time) came about since beroniga. It is also erroneous to give the quality of godness to vu since it hasn't any. Vu has always been at the mercy of the ori (the spirit gods). The ori, both good and bad often have their manifestations in trees, snakes, rivers, hills or the souls of departed parents and relatives. While tree-god may die, river-god may dry up, the ori which gave those entities the qualities of godness, never die - they reincarnate! It was at the kidori (stone altars) the Madi people worship ori. In Madi worship is called kirodi di ka (or sometimes vu di ka). When the ori are happy with the people they bless vu, and vu becomes friendly to the inhabitants.

Islam

The majority of the Madi are now Christians, while some are Muslim. Most Christian Ma'di are Catholics with some Anglicans. However a plethora of new churches are springing up daily in the area.

There is also a sizeable Moslem community, mostly of Nubi (in Uganda), especially in trading areas like Adjumani, Dzaipi and Nimule. See Juma Oris and Moses Ali. However, even the so-called 'people of the books' often revert to traditional beliefs and practices at traumatic moments. In addition some modern people continue to believe in traditional African religions.

Governance The social and political set-up of the Madi is closely interwoven with spirituality and this forms their attitudes and traditions. The society is organized in chiefdoms headed by a hereditary chief known as the Opi. The Opi exercised both political and religious powers. The rain-makers, land chiefs – vudipi (who exercises an important influence over the land) and the chiefs are believed to retain similar powers even after their deaths. There was a hierarchy of spirits corresponding exactly to the hierarchy of authority as it existed in the society. The Opi (Chief/King) is the highest Authority in Madi, he is followed in rank by the community of elders who are responsible for resolving disputes, in the clans/villages. Historically the office an opi has always been held by a man. There is no record of a female opi.

Legend has it that in the past, a person only needed a seed of grain to pound to provide a meal for a whole family. One day, when the farming population had gone to their farms and the blacksmiths as usual were left all alone at home, greed took hold of them. They wanted more than the single seed the farming community gave them for their services. So on this fateful day, they stole and pounded a mortarful of grain. The gods reacted swiftly and harshly to this disobedience; a single grain seed was never again to be enough. Human beings had to (toil harder for an ever decreasing yield per grain seed. When twins are born, the first of the pair is called opt 'chief (or the related form opia for a female) and the second of the pair is eremugo 'blacksmith' (or muja for a female second twin). The blacksmith is there to provide for the chief.

The main economic activity that the Ma'di have traditionally engaged in is agriculture. The prevalence of tsetse fly depleted the livestock population at the end of the nineteenth century. Almost the whole population live off the land planting and growing mostly seasonal food crops like sesame, groundnuts, cassava, sweet potatoes, maize, millet and sorghum. Most of these are for personal consumption; only the excess is sold for cash. The main cash crops grown are cotton in Uganda and tobacco in the Sudan.

Those who live close by the Nile do some fishing for commercial purposes. The main fishing grounds are Laropi (Uganda) and Nimule (South Sudan). Most of the fish caught in Nimule is smoke dried and transported to be sold in Juba, the capital of South Sudan. An important seasonal activity used to be hunting. This has dwindled in importance partly because of curbing of hunting by governments, and partly because Nimule is designated as a National Park, making it illegal to hum in or around it. The hunting season used to be the dry season when most of the agricultural activities for the year have been completed and the grass is dry enough to be burned.

Blacksmiths have a particular significance in regard to the Ma'di. The Ma'di were at one time associated with the 'Ma'di hoc', which was once used as currency in marriages by both the Ma'di and the neighbouring tribes like the Acholi. who call it kweri ma'di 'Ma'di hoe. This was made by the blacksmiths (eremu). However, the Ma'di have low opinions of the blacksmiths, despite the important economic role they play in the society. They are thought to be a lazy lot who spend the whole day in the shed while the rest are toiling in the hot sun. They are also blamed for the fall of mankind from grace.

The Madi society is established on the notions of clans and kinship under traditional rulers which all the subjects in the same geographical area pay their allegiance. There are clan and village leaders and family units who ensure that law and order within communities are kept and maintained socially, people do not worry within close relations, communal field work, feasts, hunting and funerals take place which brings about consolidation of unity, cooperation and peace. Marriages normally take place in churches, in homes of bridegrooms and in the government Administrators office. Traditional shrines are respected. Hereditary rulers and their spouses are buried in those sacred places (rudu).

The end of the first war in 1972 brought some development to Madi land. The opening up of tobacco farms and other agricultural activities had prospects to social and economic transformation. The concluded long running civil war however forced most of the Madi people to abandon their homes and migrate to Uganda where they are living either among their relatives in Moyo and Adjumani or in refugee camps.

Sources: