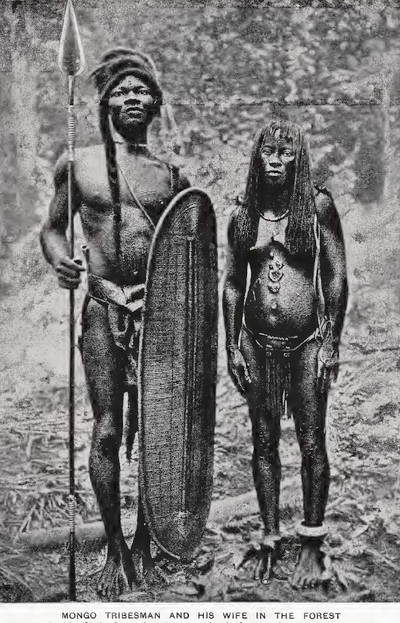

The Mongo people are a Bantu ethnic group who live in the equatorial forest of Central Africa.

The total population is about 12 million and they are the second largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, highly influential in its north region. A diverse collection of sub-ethnic groups, they are mostly residents of a region north of the Kasai and the Sankuru Rivers, south of the main Congo River bend. Their highest presence is in the province of Équateur and the northern parts of the Bandundu Province.

The Mongo people, despite their diversity, share a common legend wherein they believe that they are the descendants of a single ancestor named Mongo. They also share similarities in their language and social organization, but also have differences.

Anthropologists first proposed the Mongo unity as an ethnic group in 1938 particularly by Boelaert, followed by a major corpus on Mongo people in 1944 by Vanderkerken – then the governor of Équateur.

The Mongo people traditionally speak the Mongo language (also called Nkundo) or one of the related languages in the Bantu Mongo family, in the Niger-Congo family of languages. The Lingala language, however, often replaces Mongo in urban centers. This language has about 200 dialects, and these are found clustered regionally as well as based on Mongo sub-ethnic groups such as Bolia, Bokote, Bongandu, Ekonda, Iyaelima, Konda, Mbole, Mpama, Nkutu, Ntomba, Sengele, Songomeno, Dengese and Tetela-Kusu, Bakutu, Boyela and many others.

Mongo tribes are any of several peoples living in the African equatorial forest, south of the main Congo River bend and north of the Kasai and Sankuru rivers in Congo (Kinshasa).

They include such ethnic groups as:

The Mongo inhabit the Congo Basin of Democratic Republic of the Congo which is characterized by high temperature, abundant rainfall, and high humidity. Equatorial forests cover more than 1,040,000 square kilometers of the 3.9 million square kilometers of the basin. The distribution of flora and fauna is uneven, however, creating local habitats that have led to variations in human life-styles.

According to the historian Samuel Nelson, “the appellation “Mongo” is a relatively recent social identity that is more often utilized by outsiders than it is by the residents of the basin who generally continue to identify and think of themselves in more localized terms (Nelson 1994: 18). Anthropologists divide these localized identities into the following three: 1) northern Mongo (further divided into Balolo, Bamongo, Bomongo, Mbongo, and Lolo); 2) central Mongo (consisting of Nkundu, Mbole, Bosaka); and 3) southern Mongo (mainly the Ekonda and Kutshu). This culture summary focuses mostly on the Nkundu (central Mongo), Boyela (northern Mongo), and Ntomba and Ekonda (southern Mongo). Mongo-speaking ethnic minorities such as the Twa are excluded.

As of the 1970s, there were 216,000 speakers of the Nkundu dialect which is also referred in English sources as “Mongo proper” (Welmers 1971). By 1995, this number was estimated to be 400,000 speakers (Gordon 2005). The corresponding estimate for speakers of the entire cluster of Mongo dialects in 1970s was 3,200,000 speakers (Hayes, Ornstein, and Gage 1977).

The Mongo language consists of a cluster of dialects the most important of which includes Mongo-Nkundu, Longombe, Konda, Ngando, Ombo and Lalia. Mongo is a Bantu language belonging to the Niger-Kordofanian of the Niger-Congo family of languages (Gordon 2005).

The colonial experience and the independence that followed drastically changed Mongo culture, as well as the cultures of all of the other indigenous peoples of the Congo. Many traditional Mongo beliefs and practices have survived, and they continue to be prevalent within the wider Congolese society today, despite the pressures to assimilate to the national culture. Clearly, the Mongo participate in the national economy and work within a national labor force. They attend private or nationalized schools, and they have converted to Christianity in large numbers. It also seems clear that the Mongo have retained their tribal or ethnic identity, which implies the survival of key aspects of their traditional culture.

The Mongo began to enter the central part of the Congo Basin around the first century AD. The first migrants probably settled in the most favorable ecological niches, mainly along rivers, where fishing became a major productive activity. Other groups moved inland to engage in hunting and yam farming. The banana, which produced larger food harvests than the yam, became a staple crop around AD 1000.

The Mongo live in settled communities often consisting of one to six hamlets separated by bush and swidden fields. Each hamlet is composed of a double row of dwellings arranged close together on either side of a single road. Near many Mongo communities there is a settlement of dependent Twa. Some settlements have a kind of clubhouse where unmarried men spend time.

By the nineteenth century, agriculture had become an important part of Mongo subsistence activities. Maize, groundnuts, and beans were introduced to Central Africa by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, augmenting the established staples of yams, bananas, oil palms, and other crops. Some foodstuffs and medicinal plants, such as sweet bananas, hot peppers, and indigenous greens, were grown in small homesite gardens established near residences. Major crops, such as yams and bananas, were cultivated in larger fields, farther away from the homestead. The Mongo practiced shifting agriculture by rotating fields. After three to five years of cultivation, new fields were cleared, and the old fields were left to be reclaimed by tropical vegetation.

Gathering natural resources and foodstuffs was and still is an important subsistence activity. The Mongo harvest a wide range of products from the equatorial forest: wild fruits, vegetables, palm kernels, mushrooms, snails, and edible insects (e.g., caterpillars, termites), as well as roots and vegetation used for beverages, spices, and medicines. Products harvested from the Elaeis oil palm are especially important.

Traditionally, small animals were trapped using ropes with nooses. Larger animals, such as antelopes, boars, and elephants, were tracked and hunted by groups of men with nets, bows and arrows, and long stabbing spears. Small hunting expeditions were mounted year-round by groups of young men, and special celebrations or feasts were often marked by village-wide hunts.

The Mongo manufacture a wide variety of tools and weapons used for hunting, fishing, farming and food processing. Hiroaki Sato who surveyed Mongo hunting practices in 1976 lists a variety of arrows, bows, nets, and traps often made with local materials (Sato 1983).

According to Nelson (1994), the Mongo were only marginally involved and affected by international trade in slaves and ivory which reached the Congo Basin beginning in the eighteenth century. But they were directly affected later in the nineteenth century as the success of this trade lured outsiders into the basin for the first time, ultimately resulting in the conquest of the Congo by Belgian colonialists from 1880s-1960. In the course of this occupation, the Mongo, like many other Africans, adjusted their work patterns to adapt to changing demands and opportunities associated with international commerce in rubber, palms and other forest products.

The Mongo were also active participants in a wider inter-ethnic trade within the Congo Basin. They obtain imported good and fish from the boat owning “water people” along the Congo River in exchange for agricultural and forest products (Nelson 1994:30).

Men are responsible for managing their households, constructing homes, manufacturing assorted tools, weapons, and utensils. In addition to cooking, housekeeping and child care, women gather wild plants, plant most crops, hoe, harvest, and do practically all other agricultural work. Women also engage themselves in fishing especially during the dry season when streams are at their lowest. The men clear the land and plant bananas. Hunting and trapping are also done exclusively by men.

Land in traditional Mongo society was owned collectively by patriclans. Individual men acquired usufruct rights over plots they brought under cultivation. All members of the community were entitled to use the forest which was regarded as “a relics of the ancestors” (Nelson 1994: 37).

The Mongo are a patrilineal society. Members of each patrilineage (ilongo) often live in the same village. Patrilineages, which are exogamous with respect to both sex and marriage, are aggregated into clans. Clan members live dispersed across several villages, but form a political group under the leadership of a head from the senior lineage.

The Mongo use distinctive terms for kin on the mother's side and kin on the father's side in Ego's generation and the first ascending generation.

The Mongo have several modes of marriage to choose from. The commonest mode of marriage is parentally arranged, often by sending a formal intermediary. This type of marriage usually involves substantial bride price to be paid in skins, iron knives and/or copper rings, and, in the past, male slaves. The bride price is paid to the bride’s father who may in turn use it to obtain a wife for his own son.

Other modes of marriage include widow inheritance, exchange of sisters by two men in lieu of a bride price, and free gift of a woman in marriage without a bride price. Polygyny is common, but a man rarely has two or at most four wives.

The ideal domestic unit in Mongo society is a three-generation patrilocal extended family locally called known as linkudu. The average size of a domestic group was generally between twenty and forty members. Each domestic group was largely autonomous in its internal affairs and was led by a senior elder, who was commonly referred to as Tata or “Father.” The compounds of several neighboring domestic groups generally formed a village.

Family property is transmitted down to children by seniority. Succession to leadership position is patrilineal by seniority.

As the primary residential and economic unit of Mongo society, the domestic group also functions as the basic agency for socializing children. Children of polygamist domestic groups live with their respective mothers, who must provide their sustenance and take care of them. Children are expected to respect their parents and show affection to all siblings. Children learn a great deal from experience by helping parents. In the course of this interaction, parents teach them rules of politeness and other important social norms. Failure to follow parental orders or other appropriate behavioral codes causes reprimands and corporal punishments.

Villages usually ranged in size from 100 to 300 people. As a cohesive unit, the village undertook certain large tasks, such as clearing the forest, and formed a defensive unit against outside attacks. Community affairs were administered by a council of compound elders and the bokulaka (village chief), an elder who had received the council's recognition as group leader. In times of war and instability, dispersed Mongo villages often formed districts, which were essentially territorial alliances intended to provide for a stronger common defense. In contrast to the situation in the villages, decisions at the district level were made by a loose collection of village chiefs, other prominent male seniors, and medicine men, who were respected for their war magic and divination skills.

Most slaves were captured as a consequence of small-scale warfare. Separated from the protection of their kin, slaves had no rights. They were completely dependent on their patrons—politically, economically, and socially. In most cases, slaves were well treated even though they remained socially inferior. Their loyalty was ensured through controlled assimilation by their masters, who provided the slaves with wives and land. Masters also protected their slaves from the abuse and exploitation of others.

The Mongo distinguished gradations in social status in three broad categories: those with authority, those with inferior status, and those with no voice at all in local matters. At the top of village society were the leaders of compounds, who were the dominant “big-men” of the Mongo. They administered the internal affairs of their compounds, delegated tasks and managed food production, acted as arbitrators of disputes, and represented the compounds to the outside world. Within the villages, they formed the councils of elders that governed according to ancestral laws and regulated external relations. These village leaders held special signs of office, consumed the best portions of the hunt, had the most wives, and received respect and deference from the entire community.

There were several categories of people with inferior status in Mongo society. The largest group with low status were the women, who clearly occupied a lower social rung than the men. Although economically incorporated into her husband's family, a wife remained a member of her own family politically, and she had little say in the larger issues concerning the community. Women were given the monotonous task of gathering foods and forest products; men gathered only the items that were considered more prestigious. With few exceptions, women did not possess individual property and could not dispose of the fruits of their labor without the consent of their husbands. They also received harsher penalties than men for social infractions such as adultery.

Refugees, maternal kin, and slaves were other groups with low status in Mongo society. They were all considered inferior to the resident kin group and were dependent upon the reigning big-men. The refugees were groups of people, usually comprising one or two household compounds, who had fled their homes because of war, famine, or epidemics. Groups or individuals sometimes left their own household compounds to find refuge with their maternal kin for personal reasons (such as being denied bride-price or being obliged to leave following serious offenses, such as murder).

Kinship and seniority were both important in Mongo society. Political authority was based on wealth, but it was legitimized according to genealogical descent. Once established, big-men maintained or increased their power through land allocation, matrimonial exchange, and rights of appropriation, which were all expressed in terms of kinship and seniority. Young men were expected to follow the direction of their elders because they, too, would eventually inherit positions of power and prestige.

Each hamlet was governed by a head belonging to the senior extended family in the settlement. In doing so, the hamlet head was assisted by a council consisting of the heads of all extended families (domestic groups) residing in the hamlet. Public opinion and lineage elders are important in enforcing cultural norms relating to kinship regulation of sex and feuds.

In the pre-colonial times, intertribal and intra-tribal warfare were common. The causes were usually to avenge an uncompensated murder or settle an unresolved dispute.

The worship of ancestors played a central part in the traditional religion of the Mongo. People believed in a number of different deities and spirits, including a Supreme Being, but these were approachable only through the intervention of deceased elders and relatives. Prayers for healthy children, success in battle, or safe journeys were therefore addressed to the ancestors. The practice of witchcraft was also a part of Mongo culture. Villagers attributed most types of misfortune—including illness, infertility, bad luck, or extreme poverty—to spells or charms in operation against them. These, in turn, were most often attributed to a competitor's greed, ambition, or hatred. At the same time, significant good fortune or success was perceived to be linked to the possession of beneficial charms and amulets, of which the magician possessed more than anyone else in the village.

Ideological and moral principles and social reality are mirrored in the culture of the Mongo, particularly in their oral literature, which includes histories, folktales, proverbs, poems, songs, and greetings. Traditional folktales, which were usually centered on a moral or a piece of wisdom, were an essential part of a child's education, and proverbs dealt with all aspects of life, although the ideals of mutual obligation, respect for authority, and the importance of the family were particularly stressed.

Lineage elders perform a wide variety of religious functions because of Mongo religion’s strong emphasis on ancestor worship. Other religious practitioners include sorcerers, magicians and diviners who are believed to help or harm people by manipulating the powers of spirits.

Ancestors are remembered and honored with prayers and sacrifices. Lineage members organize seclusion-ending festivals for new mothers who are secluded from their husbands after delivery as they also do for grieving spouses. Naming and circumcision involve very little festivity.

The Mongo have a rich verbal art which includes a wide variety of folktales, proverbs, poems, and songs. They also admire elaborated body decoration and colorful ornaments including brass rings, beads, and decorated knives.

The Mongo attribute diseases to malevolent spirits. They also recognize magicians and witches who could produce powerful spells and charms by communicating with spirits. As a consequence, the Mongo seek to reverse misfortunes, including illness, infertility and bad luck, by consulting mediums who would prescribe charms, spells and prayers.

Each clan has a designated cemetery where deceased members are buried. Male burials involve no ceremony or special rules. The corpse of women who are wives within the clan must be ceremonially transported to their respective birth village in order to be buried in the clan cemetery there. However, a husband may obtain his clan’s permission to bury a deceased wife in the clan cemetery by paying required fees. Mourning for a deceased spouse requires observing several taboos and seclusion for some time

Sources: