The Oromo people (Oromo: Oromoo; English: Oromo, ’Oromo) are an ethnic group inhabiting Ethiopia. They are one of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia and represent 34.5% of Ethiopia's population.

The Oromo, are the largest, most widely dispersed people group in Ethiopia. The Oromo are composed of approximately a dozen tribal clusters. Nearly all the Oromo speak mutually intelligible dialects of the Oromo language. Although they retain similarities in their descent system, they differ considerably in religion, lifestyle, and political organization.

Hararghe Oromo are the descendants of the Barentu confederacy that moved toward the east of the Ganale River during the Oromo migration of the 16th century. They consist of the Ittu, Ania, Ala, Nole, Jarso and Babile tribes. They were able to occupy the land of the Harar uplands where they came in contact with the Somali and the Harar city-state. They became sedentary agriculturalists. Some of their tribes like the Nole and the Babile live mixed together with the Somali. (Population 7,743,000 individuals. The Joshua Project, 2023)

Arsi Oromo is an ethnic Oromo branch, inhabiting the Arsi, West Arsi and Bale Zones of the Oromia Region of Ethiopia, as well as in the Adami Tullu and Jido Kombolcha woreda of East Shewa Zone and also some of arsi clans live in other ethinic groups such as Kambata and Hadiya.They Arsi are made up of the Sikkoo-Mandoo branch of Barento Oromo. The Arsi in all zones speaks Oromo share the same culture, traditions and identity with other subgroup Oromo. (Population 6,944,000 individuals. The Joshua Project, 2023)

The Arsi have developed a concept of Arsooma which roughly translates to Arsihood. This has provided Arsi with an identity that has been passing to clans and other groupings for a long period of time. The Arsi have a complex concept of clan division. The two main branches are Mandoo and Sikko. Mandoo refers to the Arsis in the Arsi and northern Bale Zones, while Sikko refers to those mainly in the Bale Zone.

Oromos speak the Oromo language as a mother tongue (also called Afaan Oromoo and Oromiffa) which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. The word Oromo appeared in European literature for the first time in 1893 and slowly became common in the second half of the 20th century.

The Oromo people followed their traditional religion and used the gadaa system of governance. A leader elected by the gadaa system remains in power only for 8 years, with an election taking place at the end of those 8 years. From the 18th century to the 19th century, Oromos were the dominant influence in northern Ethiopia during the Zemene Mesafint period. They have been one of the parties to historic migrations, and wars particularly with northern Christians and with southern and eastern Muslims, in the Horn of Africa

LanguageThe traditional Oromo language is Oromiffa, the written form of which has recently changed to use the Roman alphabet. Oromiffa was banned during the regime of Haile Selassie, and Amharic was the only language taught in schools or used in the public sphere for decades. Thus Oromos who had formal education or grew up in urban areas can speak and write Amharic, while people in the countryside who were isolated from educational campaigns have continued to speak Oromiffa. Some Oromos may also speak Tigrigna, Somali, Arabic, or Swahili, but most Oromo refugees prefer to speak Oromiffa as a matter of cultural pride. Literacy in English is limited but growing as more people take English as a Second Language (ESL) classes.

NamingEach person has one main name, their given name. They are often given other personal “love names” by family members. Their second name is the main name of their father. A third name is usually the name of their paternal grandfather. |

|

Traditionally, the father picks Oromo children’s names but the mother has great influence in naming the daughter of the family. It must also be said that Oromo names have meanings as if to convey wishes of success, wisdom, and prosperity through generations. For instance, the most popular Oromo names are Ibsaa for males and Ibsituu for females, both meaning “light”.

Status, Role, PrestigeOromos view advance in age with great respect. The “Gadaa system”, an Oromo traditional government, is based on age grade system. For instance, to take full responsibility for a nation or society “Abbaa Gadaa” (the leader/President) reaches full leadership only at age 40 or on eighth Gadaa. (The Oromo people use base eight as opposed to the traditional Western base ten.) Oromos have a tradition of viewing long age as accumulation of wisdom gained from experience. Therefore, Oromos approach elders as students would professors, ready to learn. The elder of the village or the household is a leader of a given domain and perhaps beyond. Responsibilities, light or heavy, are assigned to persons according to how old the person is. The older the person, the less physical responsibilities, such as farming, heavy lifting, etc. are given. Physical responsibilities are usually assigned to the young, physically strong and able. Elders are given the task of thinking, conveying and radiating wisdom as needed. |

|

When issues such as weddings, death, or disputes arise, the most able and senior of elders are assembled. Issues can be won or lost on the credibility and ability of the elders, much like the quality of counsel defending or prosecuting legal cases in Western cultures.

GreetingsThe traditional greeting used by men and women is called “salamatta.” They grasp each other’s hands and kiss the top of the other person’s hands. If they are related or close friends, they would kiss each other. In the US they often shake hands in the western manner. When meeting a person on the road or street they say, “Did you have a peaceful night or day?” Children are commonly hugged when greeted. “Galla” is a derogatory term used in the past for Oromos by the ruling groups in Ethiopia. It is considered a very insulting term. Social Distance At meetings or social gatherings, Oromos commonly sit in a circle. The space between people who are speaking to each other in informal settings is commonly the same as in Western cultures. |

|

“Obbo” is the Oromiffa equivalent to “Mister“, for a married woman the term is “Ayo“, and for a young woman “Addee“. Elders are generally given great respect within their communities. Within the language there is a formal for of “you” which is used to address respected persons. Persons who are older are addressed as “mother” and “father”.

General Etiquette/Social DistanceAt meetings or gatherings Oromos normally reserve the most comfortable area for the elderly and the seniors of the group. Displays of respect for age and wisdom is expected from the audience. Respect for the start time of the meeting is also important. If a person does not respect the set time, his ideas and contribution to the group will have cold reception or he will be reminded of his/her offense from this and previous experiences. |

|

Depending on the subject matter, the young are encouraged to attend meetings as a way to teach the social etiquette and pass it on to the next generation.

Marriage is one of the most important rituals in the Oromo culture. There are three things Oromos talk about in life: birth, marriage, and death. These are the events that add to or take away from the family. Before the onset of foreign religions, namely Christianity and Islam, Oromo marriage rituals included exchange of gifts, mainly by the bride to be.

The ritual of courting begins a long time before the marriage date. It may entail encounters at events, mainly at weddings, or the courting may stem from understanding between the families. Once the boy has demonstrated responsibilities, not only for his own livelihood but also for the society in which he lives, he picks the girl he is interested in.

He will inform a family member, usually his father, who then contacts the family of the girl. Usually the girl knows of the boy’s intent and, in many instances, she encourages him to pursue her in this way. There are mediators, such as the girl’s best friends, who convey the girl’s wishes to the boy.

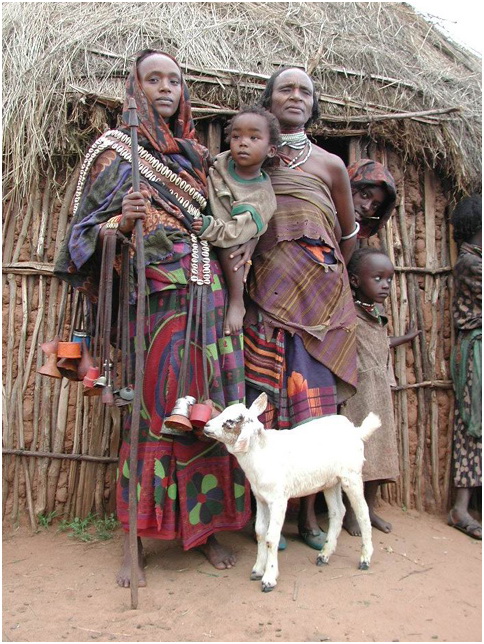

The first visit to the girl from the family of the groom-to-be involves other elders from his village. Special clothing is worn to underscore the importance of the meeting. A stick called “siinqee” is carried to the bride-to-be’s house and left at the door to indicate to her parents that the process of courting their daughter has begun in earnest. On the second visit, the “siinqee” may come in with the groom’s party indicating the girl’s family has accepted the gesture.

Visits by the groom’s party may continue over the course of two years. The visits will prepare the way for acceptance of the young man, not only by the girl’s immediate family, but by her relatives as well. It may also happen that the future son-in-law must till the land of his future in-laws – the idea is to make parents’ sure that their daughter is marrying into a family who can support their daughter and her needs.

Once the needs of all relatives are satisfied, the actual date for a marriage will be set. On the date of the wedding, gifts for the bride’s family are brought by an assembly of well-respected elders who join the wedding party. Bringing home the new bride is an all day process. Without the presence of knowledgeable elders, the marriage can be delayed.

Once the groom is home with his new bride, the wedding party may take another three or more days to complete. This is a period when the groom’s family and relatives bring presents. In old days, Oromos never married within their immediate clans, and today some Oromos continue to abide by that restriction. However, with the introduction of foreign religions and influences, times are changing the marriage traditions of the Oromo people and many Oromo marriages resemble marriages of Western or Middle Eastern cultures.

Since girls have to marry into different clans in traditional Oromo society, their relatives are almost always some distance away. Traditional Oromo wedding rituals fostered understanding and interconnectedness between different societies as well shattering a stereotypical myth that African societies were at war with one another before the arrival of foreigners, mainly Europeans and Arabs.

In Oromia, children are trained to do specific family tasks at certain age, starting at age three. Girls and boys have different roles depending on the composition of the family. Girls are taught cooking, cattle tending and gathering of firewood while boys are thought horse riding, spear throwing, hunting, farming, cattle tending and survival techniques. The Oromo culture expects men to feed, shelter, cloth and protect the family while women are expected to rear children and care for the whole family from home. Women marry starting about fifteen years of age and are expected to be virgins until then. During “Gadaa” tradition however, a young man may not marry until the age of 28, a practice that is considered “built-in” family planning.

In Oromo culture, the father is the head of the household but the true leader of the family is the mother. The day-to-day life of the family is dependent on the mother. The family may live in close proximity with other family members and relatives.

In Oromia, living in extended family households is the norm. In Seattle, Oromo family households include one to eight persons on average, and nearly half of those people are children under 12 years of age. As the refugee and immigrant Oromo population grows in the United States, attracting relatives in one area or town for support will become common.

In Oromia, women are helped through pregnancy and childbirth by female neighbors or female elders in the community. Formal prenatal care may be unfamiliar, but women traditionally increase the amount of meat in their diet and pay special attention to nutrition. If a woman was ready to deliver in Oromia, she might notify a female friend but not her husband. Men are not supposed to participate at all, and many women here are still reluctant to have their husbands involved in the birthing process.

Oromo women in Seattle have several concerns with childbirth: they are uncomfortable with male doctors and medical students, as well as with the standard American high-tech approach to anesthesia, fetal monitoring, and augmenting delivery. Many women think that American doctors are too quick to perform Cesarean sections for what the women consider normal variations, such as post-term gestational age, and they may wait at home until they are well into labor to try to avoid unwanted procedures.

After delivery, a woman is supposed to rest in bed for forty days attended by the other women of the community, who cook special foods for her and tend her other children while she regains her strength. Unfortunately, women have been unable to do that here because of school, work, and logistical problems.

In Oromia, the newborn infant’s first feedings are water for twenty-four hours, after which the baby is given fresh butter as a laxative to expel meconium and then begins to breastfeed. In Oromia, breastfeeding in public is perfectly acceptable, and the vast majority of women do breastfeed. Here, women worry that nursing in public is inappropriate, and work or school may interrupt the feeding schedule, so they are having trouble maintaining breastfeeding as long as they would like. They are unfamiliar with pumping and storing milk, but some working women may be interested in that option.

Traditionally, mothers introduced other foods at about six months of age and continued nursing until they were ready to bear another child or up to three years of age. In fact, breastfeeding was the most common means of family planning, and the shortened or incomplete breastfeeding here is contributing to a high fertility rate in Seattle’s Oromo community which taxes already stretched resources. Women may not take oral contraceptive pills correctly and dislike the spotting and subsequent amenorrhea from progesterone injections, so alternative methods of family planning are not widely practiced.

Children are considered full members of the family and of the community and are appreciated for their ability to keep their parents’ spirit present in the community even after the parents’ death. Unlike other cultural groups from Ethiopia, Oromos allow children to eat at the same table with adults and participate in discussions of significance as soon as they are old enough to talk and understand.

Discipline is achieved by teaching respect for elders from an early age, by correcting bad behavior verbally, and occasionally spanking. The fear of child protection services involvement in family affairs has made many Oromo families stop spanking or correcting their children’s unwanted and more often counter productive behavior. Many in the Seattle’s Oromo community are unsure of other methods, aside from winning and enforcing respect, to manage unwelcome behaviors.

The community as a whole is concerned about their children surviving adolescence in the United States of America without getting involved in drugs and violence. Over the years, the local Community Organization has worked on involving kids in physical activities such as running, soccer and basketball in the spring and summer, and academic support in order to occupy the times and energy of young people.

Even though many now understand and grudgingly accept teenage dating, this is a new practice to many Oromo families. In Oromia, pre-arranged marriage is the norm and many Oromo immigrants still prefer old tradition to new.

In contrast to other peoples of Africa, Oromos did not have a tribal chieftan structure. They had a democratic system of government called the “gadda”. There were 5 political groupings and each group governed for 8 years in turn taking 40 years to complete the cycle. A person who proved himself for the five stages would become the father of the country, if given the majority vote. Democratic meetings where all speak out and where the selection of local leaders are made continue today in local Oromo groups.

Women were traditionally given great respect and had a particular role in resolving conflicts respect and a prominent role in electing leaders. Physical beating of a woman by her husband was forbidden by Oromo law and a man who did this would be publicly shamed by powerful women. In Seattle, Oromo women commonly participate in discussion in community meetings and until recently, they sat mixed with men. Elders within the community are respected as counselors and advisors to the community and for resolving family disputes.

Buddeenaa, (or bideenna, several spellings have been suggested), is a fermented flat bread made from teff flour and is commonly eaten by Oromos. A spicy barley dish mixed with butter is a special delicacy. Butter is added to most porridge and stew or soup dishes. Meat is an important part of the diet, both smoked and fresh, but pork is not eaten. Milk and coffee mixed with milk are common drinks. Traditionally food is eaten with the fingers of the right hand. Western utensils may now be used in Oromo homes in Seattle.

Back home many Oromos drink homemade bear called “farsoo” or “daadhi”(alcoholic) and “qaribo” (non-alcoholic version). Other harmful drugs common in Western cultures were historically unknown to Oromos.

Traditional Oromo religious belief centers around one God, Waaqa, who is responsible for everything that happens to human beings. As Oromos adopted Islam or Christianity, they maintained the concept of Waaqa and incorporated their beliefs into the new religions. The majority of Oromos in Seattle practice Islam, reflecting a Muslim majority within Ethiopia, and they have had some difficulty maintaining their traditions in the U.S. For instance, during the month-long holiday of Ramadan, Muslims are supposed to fast all day, eat most of the night, and pay special attention to prayer, but American public schools and work places are not set up to accommodate such a schedule.

Another large percentage of Oromos are Christian. Christians are primarily Catholic or Adventist rather than Orthodox, as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is associated with the dominant Amhara cultural group. Within the Oromo nation, Muslims and Christians have mingled peacefully, as they do in the community here. Oromo Christians are less restricted in their abilities to worship as they see fit because the dominant religion in America is Christianity. Those Oromos whose traditions still mirror the traditions of “Waaqefataa” are less organized, less visible and therefore less understood.

In Oromia, when a household is faced with the reality of death, community support is given in the form of money, time, and physical labor. In Seattle, this tradition continues, as it is the only way to support the grieving families.

Traditional Oromo healers are skilled at bone-setting, cautery, minor surgical procedures such as tonsillectomy or uvulectomy for throat infections and drainage of abscesses, and treating many illnesses with medicines made from local plants. Individuals were also accustomed to using plants for home remedies for minor illnesses, but of course many familiar herbs are not found growing in Western Washington.

Hygiene is known to be important, and many diseases are recognized to be contagious, but many diverse forces are thought capable of affecting health. Illness and misfortune in general is often considered a punishment from Waaqa for sins a person has committed, and the “evil eye” is a malevolent influence from other people that can cause disease, especially in vulnerable young infants.

Endemic diseases in Oromia are similar to the rest of sub-Saharan Africa and include Hepatitis A and B, tuberculosis, falciparum malaria, syphilis, schistosomiasis and other tropical infectious diseases. AIDS is emerging as a significant problem, complicated by a social reluctance to discuss extramarital sexual activity, especially among teenagers.

Some members of the Seattle Oromo Community believe the Ethiopian government is purposely ignoring and under-funding disease control, particularly for HIV/AIDS, in Oromia regions as a political tool to either eliminate as many Oromos as possible or to further control Oromo lives.

In Oromia, circumcision is performed on both boys and girls either in early infancy or at the time of marriage. Female circumcision is desirable but optional, while male circumcision is considered mandatory for reasons of health/hygiene and social acceptance, as well as religious law for Muslims. The community is very concerned that some of their boys who were born in refugee camps still have not been circumcised, as the Department of Health and Social Service pays for them in older children only if medically indicated, and the cost for a routine procedure with general anesthesia is over two thousand dollars. The urologists at Children’s Hospital in Seattle may be willing to do the procedure with just local anesthetics in a cooperative patient but would need a special referral.

After leaving their country, most people spent some time in refugee camps in Kenya, Sudan or Somalia. Refugee arrival in the United States began in the early 1980s and peaked in 1989-90, with the largest numbers of people settling in Seattle in 1989-93. The total population in the greater Seattle area numbers about 3000 and is growing, mainly with new babies but also with a few family members still emigrating from refugee camps in Kenya.

The Oromo Community Organization was founded by members of the community to help each other build new lives in Seattle, and a main focus of the Organization right now is education and job training so that Oromos can support themselves independently without needing public assistance. The Organization is especially interested in promoting education for its women as a way of improving the health and welfare of women, children and the community as a whole.

Most of Seattle’s Oromo population lives in south Seattle (Rainier Valley and Holly Park), but some families have also settled in Ballard, West Seattle, Kent, Redmond, and Bellevue.

Most of the community comes from rural areas within Ethiopia and may have had little formal education, but many urban Oromos are well-educated and worked in nursing, teaching, or other professional fields before coming here. Oromos are working in a variety of capacities in Seattle, but unemployment and underemployment are problems for many heads of households.

Many familiar practices will be changing in the new American cultural milieu, but Oromos hope to celebrate and strengthen their own culture as they build a community here.

The Borana Oromo people, also called the Boran, are a subethnic section of the Oromo people who live in southern Ethiopia (Oromia) and northern Kenya. They speak a dialect of the Oromo language that is distinct enough that it is difficult for other Oromo speakers to understand. The Borana people are notable for their historic gadaa political system. They follow their traditional religions or (Ethiopian Orthodox) Christianity and Islam.

Demography and language. Between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, the Oromo people had differentiated into two major confederation of pastoral tribes: the Borana and the Barentu, and several minor ones. The Barentu people thereafter expanded to the eastern regions now called Hararghe, Arsi, Wello and northeastern Shawa. The Borana people, empowered by their Gadda political and military organization expanded in the other directions, regions now called western Shawa, Welega, Illubabor, Kaffa, Gamu Goffa, Sidamo and thereafter into what is now northern Kenya regions. The Borana further subdivided into various subgroups such as Macha, Tulama, Sadacha and others.

The Borana speak Borana (or afaan Booranaa), a dialect of Oromo language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family of languages. In the border regions of Ethiopia-Kenya and southwestern Somalia, one estimate places about 220,000 people as Boranas. Another estimate in 2011 suggests 177,000 Boranas in Ethiopia and 95,000 in Kenya. The Borana are the southernmost Horners of the Horn peninsula.

Society - Gadda. The Oromo people were traditionally a culturally homogeneous society with genealogical ties. The Borana and other Oromo communities governed themselves in accordance with gadaa (literally "era"), a limited democratic socio-political system long before the 16th century, when major three party wars commenced between them and the Christian kingdom to their north and Islamic sultanates to their east and south. The Gadda system elected males from five Oromo miseensa (groups), for a period of eight years, for various judicial, political, ritual and religious roles. Retirement was compulsory after the eight year term, and each major clan followed the same gadaa system. Women and people belonging to the lower Oromo castes were excluded. Male born in the upper Oromo society went through five stages of eight years, where his life established his role and status for consideration to a gadaa office.

Under gadaa, every eight years, the Oromo would choose by consensus an Abbaa Bokkuu responsible for justice, peace, judicial and ritual processes, an Abbaa Duulaa responsible as the war leader, an Abbaa Sa'aa responsible as the leader for cows, and other positions.

Social stratification. Like other ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa and East Africa, Borana Oromo people regionally developed social stratification consisting of four hierarchical strata. The highest strata were the nobles called the Borana, below them were the Gabbaro (some 17th to 19th century Ethiopian texts refer them as the dhalatta). Below these two upper castes were the despised castes of artisans, and at the lowest level were the slaves.

The Guji people belong to the Oromo ethnic group. They speak Oromo language and practice the original Oromo culture. They are, even, considered to be the ones who have sustained the original Oromo traditions. In other words, the original Oromo traditions are still active in practices of the Guji society. In their ways of life and dialect, the Guji Oromo seem to be distinct from Oromos of other parts of the country with the exception of the Borana Oromo. With the Borana Oromo, they share some ways of life and speak a relatively similar dialect (Van De Loo, 1991).

The Guji live in a large territory found in South Ethiopia at approximately, 450 k.ms. away from Addis Ababa. The area is bordering with Borana in the South, Walayta and Gamo Gofa in the West, Sidama and Gedeo in the North, and Bale and Arsi in the East. Therefore, the Guji are neighbours with the Borana, the Walayta, the Gamo, the Gedeo, the Sidama, the Aris and the Bale people.

The Guji have not been restricted to Guji territory, but have been diffused in the adjacent areas occupied by other ethnic groups. Some of them live mixed with the Gedeo and Sidama people in Gedeo and Sidama Woredas (districts) and Kebeles (villages). In the same way, they live with the Borana people in Borana dominated areas. However, they sometimes, come into conflict with their neighbours such as Walayta, Gedeo and Borana peoples mainly on account of the possession of farmland (Ibid).

According to an informant (Bahrbare Balli), the Guji tribe embraces three sub-tribes. These sub-tribes are called Huraga, Mati and Hokku. Such sub-division, of the tribe is told in Guji oral traditions. The tribal father of the Guji was known as Gujo. It seems that it was from this name that the present name of the tribe had originated. It is said that Gujo had three sons from his first wife. He named the sons Huraga, Mati and Hokku. The sons, after coming of age, married wives and begot children. As a result, the three Guji sub-tribes emerged.

Besides, the three sons of Gujo moved to a large unoccupied area and divided it among themselves. The sub-divisions were agreed upon to be called by their owners.

Accordingly, the sub division that was taken by Huraga was called Huraga, that owned by Mati was called Mati and the third Hokku. Eventually, the Guji sub-areas have been called as Huraga, Mati and Hokku. However, there are no clear cultural and linguistic distinctions among the people of these areas (the same informant).

The Guji sub –tribes could also be further divided into clans (Balbala). For example, the Hurga sub-tribe consists of seven clans: Gola, Sorbortu, Agamtu, Hallo, Darartu, Zoysut, and Galalcha. The Hokku sub-tribe includes Obborra, Bala, Buditu, Micille and Kino; whereas, the Mati Sub-tribe comprises only three clans: Hirkatu, Insale and Handoa. All the clans live scattered on the large territory of the Guji as well as adjoining lands, for example, in Gedeo and Sidama areas. There are no cultural and dialectical elements that distinguish one clan from another. All members of the tribe live mixed and scattered on the large territory without any conflict and cultural or political differences among them. They consider each other as brothers and sisters, act together in times of war and practice Gada rituals together (Van De Loo 1991, Tadesse, 1995; the same informant).

The Guji People’s Ways of Life: The Gada System

The old aged and peculiar Oromo tradition, the Gada system, is still functional and practiced by the Guji Oromo. The Oromo Gada system seems to be uncommon among Oromo in other parts of the country. However, the Guji and Borana Oromos have kept the Gada institution and its rituals fresh with its flavor. In these people, it has been serving as an institution that regulates the social, political, cultural and economic norms and events (Ibid).

The Gada institution of the Guji people involves a system of age-set and generation-set that form and enforce the social, political and cultural norms by which individuals and their collective lives are governed (Asmeron, 1973; Hinnant, 1984; Van De Loo, 1991). In other words, the Guji Gada institution is concerned with formulation of the social, political, cultural and economic orders among the people by creating sets of ritual status based on age and generation. It serves as a ritual through which each member of the Guji society is supposed to pass as well as the organization that regulates this ritual.

Each member of the people is conscious of the power and authority vested on the Gada institution and is highly obedient to its directives. Among Guji society, the Gada institution seems to be the ex-genesis of the prevalent social structures and common cultural codes (Hinnant, Ibid). Thus, it is possible to note that the Gada institution of the Guji people is a complex system of ranking, authorizing and decision making for the people.

It is made up of ten successive classes that rotate every eight years. These classes are called: Dabballe, Qarre, Kuusa, Raaba, Doori, Gadaa, Baatuu, Yuuba, Jaarsa Guduru, and Jaarsa Qulullu (Van De Loo, Ibid). The classes contain two series of five successive grades. Each grade is again supposed to go through eight years of activity. The system assigns special rights and duties for each grade or class in the period of its activity. In the system, each male member of the society is promoted to next grade once in every eight years (Ibid). In the Gada system of administration, elders were given a great responsibility. They resolve local disputes, disapprove malpractices, advise and guide the youth and mobilize the people to strengthen their solidarity.

In short, in the Guji people, the Gada institution seems to be an authorized body that generates the social, cultural and political codes, and governs the day-to-day life of the people. Van de Loo (Ibid:35) asserts “…that in the Guji , the Gada institution is the top and authorized body that governs the spiritual and material lives of the people”. Thus, all aspects of the traditional life of the Guji people are governed by laws of the Gada institution (Ibid).

Traditional Belief : Waaqefanna

The Guji people, mainly the elders, practice traditional belief that was believed to be common to most Africans in the earlier times. The majority of the people are still carrying out traditional belief that was also regarded to be the earlier and native belief of the Oromo people. The Guji traditional belief is, presently, called Waqafanna, which has been defined as a belief in one God who has created everything and above all in his power. The belief is led by Qallu who is a significant body in the Gada institution (Wataa Shedo).

In the Guji people, the Qallu is perceived as a messenger of Waaqaa (God). Every time he appears, the people pay him homage and receive his blessings. The qallu with his companions (jarroole) serves as facilitator of peace and conformity among the people.

He gives blessing and says prayers moving here and there in the Guji villages. He also serves as an agent that promotes, and reinforces the aadaa (culture), safuu (morals) and seeraa (laws) of the people. This influential person is regarded as the leader and enforcer of the Guji traditional belief (waaqafanna) as well as regulator of the social and cultural lives of the society (Wataa Shedo).

Waqafanna, as stated above is a belief in one God; the God of creation, peace and life; the God who created and guides everything; the God who created river, therefore, God of river; the God who created tree; therefore, God of trees; the God who is manifested in the form of ayanaa (kind spirit). The God who comes down to a man in the form of ayanaa (kind spirit) and helps and guides him. Therefore, a Guji father says “Ayana Abbaakoo na gargaari, i.e., God of my father help me” whenever he leaves his home to his farmland. He is praying to the God who helped and guided his forefathers. Thus, the waqafanna involves the belief in and prayer to the God who created the world and its dwellers (the same informant).

Arsi Oromo is one of the branches of Oromo people inhabiting the Oromiya Region, mainly in the Arsi and Bale Zones. They claim to have descended from a single individual called Arse. The Arsi in all zones speak the same language Afaan Oromo, and share the same cultures and traditions. Among the cultural norms observed, the concept of Wayyuu is the primary one.

Wayyuu, constituting part of the Gadaa system, is one of the major constructs in a traditional Oromo worldview and is a concept with clear religious connotations. It is reflected in various cultural practices and has played a decisive role in defining the position and the rights of women in traditional Oromo society. Among other things, seems to have played a preventive role when it comes to sexual abuse and sexual harassment.

Not easily translated into English, the following are some representations given by researchers in attempts to give meaning to the word Wayyuu: something that is sacred or something that should not be touched. The respect that is reflected in Wayyuu is not ordinary respect. It is a special respect that comes from God. It is a mutual respect. God has given respect to all things. Everything has its Wayyuu. God is also Wayyuu (Waqnii Wayyuu).

Heaven is also Wayyuu (Samii Wayyuu). As a result, people dare not speak bad things about heaven because heaven is the home of God. This is the holiest place since it is the place of God and it is Wayyuu. God is the greatest Wayyuu. He is the one who created everything. This concept of Wayyuu in Arsi Oromo is also extended to women of different status.

For instance; a female in-law is Wayyuu, a woman who gave birth to you is Wayyuu to you, co- wives of your mother is Wayyuu, a married woman is Wayyuu, a virgin girl is Wayyuu, a pregnant woman is Wayyuu, a woman who wears the Qanaffa is Wayyuu, a woman who wears Hanfala is Wayyuu and a woman who holds Siinqee is Wayyuu. The list could be extended even further. As Marit states ‘everything has its Wayyuu’. This list suggests the considerable extent to which the Arsi Oromo associate Wayyuu with women, and with material objects and locations, which belong to the female sphere. Since it is beyond the scope of this paper to embark on a detailed discussion of the various implications of the different persons and objects that are said to be Wayyuu, I will rather focus on the Wayyuu as the Siinqee stick symbolizes it.

Siinqee: Women’s customary institution in Arsi

Siinqee is a stick (Ulee) symbolizing a socially sanctioned set of rights exercised by women. The Siinqee is a special stick, which a woman who gets legally married will receive on her wedding day. My informant describes the Siinqee as ‘a woman’s weapon’, symbolizing the respect and the power that a married woman has. The Siinqee stick is given to a woman in order to protect her rights. My informant explained that: ‘if a woman has a Siinqee she has to be respected, nobody should fight with her’. Here, it is very important to note that Siinqee is applicable to women who have been married in accordance with the Gadaa system. If the marriage is concluded outside the rules and regulations of Siinqee, like in the cases of marriage by force (butta), the woman does not enjoy the protection accorded by Siinqee. On the other hand, if a woman is married based on Siinqee, like in the case of kadhacha (marriage based on agreement between two families), she has full rights to enjoy her privileges under Siinqee.

Regarding the origin of Siinqee, Tolosa states that ‘this symbolic matter [Siinqee] was handed over to Abba Gadaa by the Qallu-the ritual leader of the Oromo society in the framework of the Gadaa system’. It is believed that the Qallu gave it to the Abba Gadaa in order to hold the Bokkuu (another important wooden stick among the Oromo) for himself, and the Siinqee to his wife. Due to the strong attachment that the Oromo people have to the Gadaa system, every sanction it imposes on the society has a chance of being met with respect. Therefore, it is warranted to conclude that the value embedded in Siinqee emanates from the overall respect given to the Gadaa system, and reverence to the stick has long been associated with this respect.

It is also important to note that Siinqee is not merely a term for a material symbol, it also refers to an institution, namely to a women’s organization that excludes men, and that has both religious and political functions. Kuwee Kumsa indicates that the Siinqee institution was given to women by Gadaa laws and it was highly respected by the society. Women used to use their Siinqee in various religious, social, political and economic contexts, to protect their property rights; to assert control over sexuality and fertility; to protect their social rights and to maintain religious and moral authority.

Sources: