The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region. They are thought to have diverged from other humans 100,000 to 200,000 years ago. Their recent ancestral territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and South Africa.

San people are related to the Khoekhoe (Khoikhoi). Bushmen is an Anglicization of boesman, the Dutch and Afrikaner name for them; saan (plural) or saa (singular) is the Nama word for “bush dweller(s),” and the Nama name is now generally favoured by anthropologists.

Contrary to earlier descriptions, the San are not readily identifiable by physical features, language, or culture. In modern times, they are for the most part indistinguishable from the Khoekhoe or their Bantu-speaking neighbours. Nevertheless, a San culture did once exist and, among some groups, still exists. It centred on the band, which might comprise several families (totaling between 25 and 60 persons).

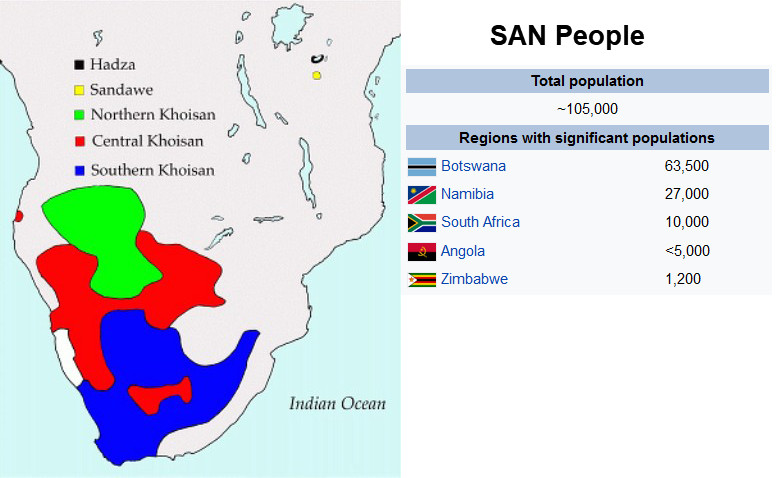

In 2017, Botswana was home to approximately 63,500 San, making it the country with the highest proportion of San people at 2.8%. 71,201 San people were enumerated in Namibia in 2023, making it the country with the second highest proportion of San people at 2.4%

In Khoekhoegowab, the term "San" has a long vowel and is spelled Sān. It is an exonym meaning "foragers" and is used in a derogatory manner to describe people too poor to have cattle. Based on observation of lifestyle, this term has been applied to speakers of three distinct language families living between the Okavango River in Botswana and Etosha National Park in northwestern Namibia, extending up into southern Angola; central peoples of most of Namibia and Botswana, extending into Zambia and Zimbabwe; and the southern people in the central Kalahari towards the Molopo River, who are the last remnant of the previously extensive indigenous peoples of southern Africa.

The designations "Bushmen" and "San" are both exonyms. The San have no collective word for themselves in their own languages. "San" comes from a derogatory Khoekhoe word used to refer to foragers without cattle or other wealth, from a root saa "picking up from the ground" + plural -n in the Haiǁom dialect.

"Bushmen" is the older cover term, but "San" was widely adopted in the West by the late 1990s. The term Bushmen, from 17th-century Dutch Bosjesmans, is still used by others and to self-identify, but is now considered pejorative or derogatory by many South Africans. In 2008, the use of boesman (the modern Afrikaans equivalent of "Bushman") in the Die Burger newspaper was brought before the Equality Court. The San Council testified that it had no objection to its use in a positive context, and the court ruled that the use of the term was not derogatory.

The San refer to themselves as their individual nations, such as ǃKung (also spelled ǃXuun, including the Juǀʼhoansi), ǀXam, Nǁnǂe (part of the ǂKhomani), Kxoe (Khwe and ǁAni), Haiǁom, Ncoakhoe, Tshuwau, , etc. Representatives of San peoples in 2003 stated their preference for the use of such individual group Gǁana and Gǀui (ǀGwi)names, where possible, over the use of the collective term San.

Adoption of the Khoekhoe term San in Western anthropology dates to the 1970s, and this remains the standard term in English-language ethnographic literature, although some authors later switched back to using the name Bus. The compound Khoisan is used to refer to the pastoralist Khoi and the foraging San collectively. It was coined by Leonhard Schulze in the 1920s and popularized by Isaac Schapera in 1930. Anthropological use of San was detached from the compound Khoisan, as it has been reported that the exonym San is perceived as a pejorative in parts of the central Kalahari. By the late 1990s, the term San was used generally by the people themselves. The adoption of the term was preceded by a number of meetings held in the 1990s where delegates debated on the adoption of a collective term. These meetings included the Common Access to Development Conference organized by the Government of Botswana held in Gaborone in 1993, the 1996 inaugural Annual General Meeting of the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) held in Namibia, and a 1997 conference in Cape Town on "Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage" organized by the University of the Western Cape. The term San is now standard in South African, and used officially in the blazon of the national coat-of-arms. The "South African San Council" representing San communities in South Africa was established as part of WIMSA in 2001.

The term Basarwa (singular Mosarwa) is used for the San collectively in Botswana. The term is a Bantu (Tswana) word meaning "those who do not rear cattle", that is, equivalent to Khoekhoe Saan. The mo-/ba- noun class prefixes are used for people; the older variant Masarwa, with the le-/ma- prefixes used for disreputable people and animals, is offensive and was changed at independence.

In Angola, they are sometimes referred to as mucancalas, or bosquímanos (a Portuguese adaptation of the Dutch term for "Bushmen"). The terms Amasili and Batwa are sometimes used for them in Zimbabwe. The San are also referred to as Batwa by Xhosa people and as Baroa by Sotho people. The Bantu term Batwa refers to any foraging tribesmen and as such overlaps with the terminology used for the "Pygmoid" Southern Twa of South-Central Africa.

San people speak numerous dialects of a group of languages known for the characteristic 'clicks' that can be heard in their pronunciation, represented in writing by symbols such as ! or /.

The San speak, or their ancestors spoke, languages of the Khoe, Tuu, and Kxʼa language families, and can be defined as a people only in contrast to neighboring pastoralists such as the Khoekhoe and descendants of more recent waves of immigration such as the Bantu, Europeans, and Asians.

The hunter-gatherer San are among the oldest cultures on Earth, and are thought to be descended from the first inhabitants of what is now Botswana and South Africa. The historical presence of the San in Botswana is particularly evident in northern Botswana's Tsodilo Hills region. San were traditionally semi-nomadic, moving seasonally within certain defined areas based on the availability of resources such as water, game aimals, and edible plants. Peoples related to or similar to the San occupied the southern shores throughout the eastern shrubland and may have formed a Sangoan continuum from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope. Early San society left a rich legacy of cave paintings across Southern Africa.: 11–12

In the Bantu expansion (2000 BC - 1000 AD), San were driven off their ancestral lands or incorporated by Bantu speaking groups.: 11–12 The San were believed to have closer connections to the old spirits of the land, and were often turned to by other societies for rainmaking, as was the case at Mapungubwe. San shamans would enter a trance and go into the spirit world themselves to capture the animals associated with rain.

By the end of the 18th century after the arrival of the Dutch, thousands of San had been killed and forced to work for the colonists. The British tried to "civilize" the San and make them adopt a more agricultural lifestyle, but were not successful. By the 1870s, the last San of the Cape were hunted to extinction, while other San were able to survive. The South African government used to issue licenses for people to hunt the San, with the last one being reportedly issued in Namibia in 1936.

From the 1950s through to the 1990s, San communities switched to farming because of government-mandated modernization programs. Despite the lifestyle changes, they have provided a wealth of information in anthropology and genetics. One broad study of African , completed in 2009, found that the genetic diversity of the San was among the top five of all 121 sampled populations. Certain San groups are one of 14 known extant "ancestral population clusters"; that is, "groups of populations with comgenetic diversitymon genetic ancestry, who share ethnicity and similarities in both their culture and the properties of their languages".

Despite some positive aspects of government development programs reported by members of San and Bakgalagadi communities in Botswana, many have spoken of a consistent sense of exclusion from government decision-making processes, and many San and Bakgalagadi have alleged experiencing ethnic discrimination on the part of the government. : 8–9 The United States Department of State described ongoing discrimination against San, or Basarwa, people in Botswana in 2013 as the "principal human rights concern" of that country.

Their social structure is not tribal because they have no paramount leader and their ties of kinship are fairly relaxed. They are a loosely knit family culture where decisions are made by universal discussion and agreement by consensus. An individual's opinion is naturally weighted according to their level of skill and experience in the particular field of discussion.

Families within a clan would speak a common language but neighboring clans would usually speak a different tongue, although there would normally be a fair degree of similarity & understanding between them. Apart from family relations, bearing the same name (out of only about 35 names per gender) would also foster a “name kinship”.

Bushmen are generally nomadic within fairly limited boundaries, governed by the proximity of other families and clans. As a very loose guideline, the territory of a family may stretch to a 25-mile circle. Obviously, if there are no other bordering clans or other people these areas may stretch further, as far as is needed to ensure adequate food and water sources.

The roles of men & women were very distinct and rarely overlapped, which is a characteristic almost universal amongst hunter/gatherers the world over. It based on survival needs encouraging the most efficient utilisation of available skills and resources. Despite what is often perceived as a very sexist society, the importance of women is very high within the group and their opinions often take precedence, particularly where food is concerned.

The San kinship system reflects their history as traditionally small mobile foraging bands. San kinship is similar to Inuit kinship, which uses the same set of terms as in European cultures but adds a name rule and an age rule for determining what terms to use. The age rule resolves any confusion arising from kinship terms, as the older of two people always decides what to call the younger. Relatively few names circulate (approximately 35 names per sex), and each child is named after a grandparent or another relative, but never their parents.

Children have no social duties besides playing, and leisure is very important to San of all ages. Large amounts of time are spent in conversation, joking, music, and sacred dances. Women may be leaders of their own family groups. They may also make important family and group decisions and claim ownership of water holes and foraging areas. Women are mainly involved in the gathering of food, but sometimes also partake in hunting.

Water is important in San life. During long droughts, they make use of sip wells in order to collect water. To make a sip well, a San scrapes a deep hole where the sand is damp, and inserts a long hollow grass stem into the hole. An empty ostrich egg is used to collect the water. Water is sucked into the straw from the sand, into the mouth, and then travels down another straw into the ostrich egg.

Traditionally, the San were an egalitarian society. Although they had hereditary chiefs, their authority was limited. The San made decisions among themselves by consensus, with women treated as relative equals in decision making. San economy was a gift economy, based on giving each other gifts regularly rather than on trading or purchasing goods and services.

As of 1994, about 95% of San relationships were monogamous.

The San have no formal authority figure or chief, but govern themselves by group consensus. Disputes are resolved through lengthy discussions where all involved have a chance to make their thoughts heard until some agreement is reached.

Certain individuals may assume leadership in specific spheres in which they excel, such as hunting or healing rituals, but they cannot achieve positions of general influence or power. White colonists found this very confusing when they tried to establish treaties with the San. Leadership among the San is kept for those who have lived within that group for a long time, who have achieved a respectable age, and good character. San are largely egalitarian, sharing such things as meat and tobacco.

Land is usually owned by a group, and rights to land are usually inherited bilaterally. Kinship bonds provide the basic framework for political models. Membership in a group is determined by residency. As long as a person lives on the land of his group he maintains his membership. It is possible to hunt on land not owned by the group, but permission must be obtained from the owners.

The elementary family within the band is composed of husband, wife, and their dependent children, but it is occasionally enlarged by polygynous marriage. Often all band members are related. Considerable interaction through trade, visiting, and particularly marriage may take place between bands; and kinship, both real and fictional, has wide ramifications, thus facilitating the frequent movement of people from band to band, so that the composition of any particular band may fluctuate considerably in time. Each band is an autonomous, somewhat leaderless unit within its own territory, and in most bands influence rather than authority is exercised in particular situations by skilled hunters or older men.

Many of the rural San live in lightweight, semicircular structures of branches laced with twigs and thatched with grass. Their equipment is portable, their possessions few and lightweight. Woods, reeds, and animals (and, formerly, stone) are the main raw materials from which their skin clothing, carrying bags, water containers, and hunting weapons are made. For hunting they use bows and poisoned arrows, snares, throwing sticks, and sometimes spears. They have probably always fed on game, wild vegetables, fruits, nuts, and insects; as game becomes less plentiful, they are forced to rely increasingly on gathering or, ultimately, into abandoning their old means of subsistence altogether.

Villages range in sturdiness from nightly rain shelters in the warm spring (when people move constantly in search of budding greens), to formalized rings, wherein people congregate in the dry season around permanent waterholes. Early spring is the hardest season: a hot dry period following the cool, dry winter. Most plants still are dead or dormant, and supplies of autumn nuts are exhausted. Meat is particularly important in the dry months when wildlife cannot range far from the receding waters.

Women gather fruit, berries, tubers, bush onions, and other plant materials for the band's consumption. Ostrich eggs are gathered, and the empty shells are used as water containers. Insects provide perhaps 10% of animal proteins consumed, most often during the dry season. Depending on location, the San consume 18 to 104 species, including grasshoppers, beetles, caterpillars, moths, butterflies, and termites.

Women's traditional gathering gear is simple and effective: a hide sling, a blanket, a cloak called a kaross to carry foods, firewood, smaller bags, a digging stick, and perhaps, a smaller version of the kaross to carry a baby.

Men, and presumably women when they accompany them, hunt in long, laborious tracking excursions. They kill their game using bow and arrows and spears tipped in diamphotoxin, a slow-acting arrow poison produced by beetle larvae of the genus Diamphidia.

Most Kalahari Bushmen believe in a "Greater" and a "Lesser" Supreme being or God. There are other supernatural beings as well, and the spirits of the dead.

The "God" or supreme being first created himself, then the land and its food, the water and air. He is generally a good power, that protects and wards of disease and teaches people skills. However, when he is angered, he can send bad fortune. The greater god, depending on his manifestation, is called different names by the same people at different times, and also have different names among the different language groups.

The lesser god is regarded as bad or/and evil, a black magician, a destroyer rather than builder, and a bearer of bad luck and disease. Just like the "supreme being" he is called by various names. They believe bad luck and disease is caused by the spirits of the dead, because they want to bring the living to the same place they are. Similar to the black people in South Africa, the Bushman have a strong believe that the ancestral spirits play an important role in the fate of the living, but they don't use the same rituals to appease them.

Cagn is the name the Bushmen gave their god; the first sociologists translated this as “Mantis”, maybe wrongly. This god being nothing else than the unseen presence of nature and everything that surrounded them. They also prayed to the moon and the stars but they could never explain exactly why they did this. Cagn was seen as human like and also had magical powers and charms.

The religions of two San groups, the !Kung and the |Gui, seem to be similar, in that both groups believe in two supernatural beings, one of which is the creator of the world and of living things whereas the other has lesser powers but is partly an agent of sickness and death. The !Kung and the |Gui also believe in spirits of the dead but do not practice ancestor worship as do many Bantu-speakers.

The San prayed to the Sun and Moon. Many myths are described to various stars.

To enter the spirit world, trance has to be initiated by a shaman through the hunting of a tutelary spirit or power animal.[7] The eland often serves as power animal. The fat of the eland is used symbolically in many rituals including initiations and rites of passage. Other animals such as giraffe, kudu and hartebeest can also serve this function.

One of the most important rituals in the San religion is the great dance, or the trance dance. This dance typically takes a circular form, with women clapping and singing and men dancing rhythmically. Although there is no evidence that the Kalahari San use hallucinogens regularly, student shaman may use hallucinogens to go into trance for the first time.

Psychologists have investigated hallucinations and altered states of consciousness in neuropsychology. They found that entoptic phenomena can occur through rhythmic dancing, music, sensory deprivation, hyperventilation, prolonged and intense concentration and migraines. The psychological approach explains rock art through three trance phases. In the first phase of trance an altered state of consciousness would come about. People would experience geometric shapes commonly known as entoptic phenomena. These would include zigzags, chevrons, dots, flecks, grids, vortices and U-shapes. These shapes can be found especially in rock engravings of Southern Africa.

During the second phase of trance people try to make sense of the entoptic phenomena. They would elaborate the shape they had 'seen' until they had created something that looked familiar to them. Shamans experiencing the second phase of trance would incorporate the natural world into their entoptic phenomena, visualizing honeycombs or other familiar shapes.

In the third phase a radical transformation occurs in mental imagery. The most noticeable change is that the shaman becomes part of the experience. Subjects under laboratory conditions have found that they experience sliding down a rotating tunnel, entering caves or holes in the ground. People in the third phase begin to lose their grip on reality and hallucinate monsters and animals of strong emotional content. In this phase, therianthropes in rock painting can be explained as heightened sensory awareness that gives one the feeling that they have undergone a physical transformation.

A San trance dance featuring the San of Ghanzi, Botswana appeared in BBC Television's Around the World in 80 Faiths on 16 January 2009.

Until recently, most amateur and professional anthropologists looked at a rock painting of the San and believed that they could decipher it without any problems. The pieces that they did not understand were passed off as crude art or that the artist had too much to drink or smoke. This has been found not to be the case, and their work is recognised as holding deep spiritual and religious meaning.

Contrary to popular belief, these paintings and engravings of strange human figures and animals, especially the Eland (a species of antelope), did not depict every day life but had a deeper religious and symbolic meaning. Gender roles are not jealously guarded in the San society. Women sometimes assist in the hunt and the men sometimes help gather plant foods.

When shaman (medicine men) painted an Eland, they did not just pay respect to a sacred animal; they also harnessed its essence (N!um). By putting paint to rock, they would be able to open portals to the spirit world. San rock paintings are found in rocky areas of the KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and the Western Cape provinces.

The San mainly used red, ranging from orange to brown, white, black and yellow in their paintings. Blue and green were never used. Red was derived from haematite (red ochre), and yellow from limonite (yellow ochre).

Manganese oxide and charcoal were used for black; white, which does not preserve well, was probably obtained from bird droppings or kaolin. The blood of an Eland, an animal of great religious and symbolic significance, was often mixed into the colour pigments.

Another striking feature of the rock art is the embodiment of action and speed. Human figures are stylized and depicted as having long strides and the animals are either galloping or leaping, or, more subtly, flicking a tail or twisting a neck. Most of the paintings have an underlying spiritual theme and are believed to have been representations of religious ceremonies and rituals.

The San are excellent hunters. Although they do a fair amount of trapping, the best method of hunting is with bow and arrow. The San arrow does not kill the animal straight away. It is the deadly poison, which eventually causes the death. In the case of small antelope such as Duiker or Steenbok, a couple of hours may elapse before death.

For larger antelope, this could be 7 to 12 hours. For large game, such as Giraffe it could take as long as 3 days. Today the San make the poison from the larvae of a small beetle but will also use poison from plants, such as the euphorbia, and snake venom.

A caterpillar, reddish yellow in colour and about three-quarters of an inch long, called ka or ngwa is also used. The poison is boiled repeatedly until it looks like red currant jelly. It is then allowed to cool and ready to be smeared on the arrows.

The poison is highly toxic and is greatly feared by the San themselves; the arrow points are therefore reversed so that the poison is safely contained within the reed collar. It is also never smeared on the point but just below it - thus preventing fatal accidents.

The poison is neuro toxic and does not contaminate the whole animal. The spot where the arrow strikes is cut out and thrown away, but the rest of the meat is fit to eat. The effect of the poison is not instantaneous, and the hunters frequently have to track the animal for a few days.

The San also dug pitfalls near the larger rivers where the game came to drink. The pitfalls were large and deep, narrowing like a funnel towards the bottom, in the centre of which was planted a sharp stake. These pitfalls were cleverly covered with branches, which resulted in the animals walking over the pit and falling onto the stake.

When catching small animals such as hares, guinea fowls, Steenbok or Duiker, traps made of twisted gut or fibre from plants were used. These had a running noose that strangled the animal when it stepped into the snare to collect the food that had been placed inside it. Another way of capturing animals was to wait at Aardvark holes.

Aardvark holes are used by small buck as a resting place to escape the midday sun. The hunter waited patiently behind the hole until the animal left. When this happened, it was be firmly pinned and hit on the head with a Kerrie (club).

The San are intelligent trackers and know the habits of their prey. On discovering where a herd has gathered, they immediately test the direction and force of the wind by throwing a handful of dust into the air. If the ground is bare and open, he will crawl on his belly, sometimes holding a small bush in front of him.

Hunters carry a skin bag slung around one shoulder, containing personal belongings, poison, medicine, flywhisks and additional arrows. They may also carry a club to throw at and stun small game, a long probing stick to extract hares from their burrows or a stick to dig out Aardvark or Warthog.

Hunting is a team effort and the man whose arrow killed the animal has the right to distribute the meat to the tribe members and visitors who, after hearing about the kill, would arrive soon afterwards to share in the feast. According to San tradition, they were welcome to share the meal and would, in the future, have to respond in the same way. However, plant foods, gathered by the womenfolk, are not shared but eaten by the woman's immediate family.

The San make use of over 100 edible species of plant. While the men hunt, the women, who are experts in foraging for edible mushrooms, bulbs, berries and melons, gather food for the family. Children stay at home to be watched over by those remaining in camp, but nursing children are carried on these gathering trips, adding to the load the women must carry.

The San belief system generally observes the supremacy of one powerful god, while at the same time recognizing the presence of lesser gods along with their wives and children. Homage is also paid to the spirits of the deceased. Among some San, it is believed that working the soil is contrary to the world order established by the god.

Some groups also revere the moon. The most important spiritual being to the southern San was /Kaggen, the trickster-deity. He created many things, and appears in numerous myths where he can be foolish or wise, tiresome or helpful.

The word '/Kaggen' can be translated as 'mantis', this led to the belief that the San worshipped the praying mantis. However, /Kaggen is not always a praying mantis, as the mantis is only one of his manifestations. He can also turn into an Eland, a hare, a snake or a vulture - he can assume many forms. When he is not in one of his animal forms, /Kaggen lives his life as an ordinary San.

A ritual is held where the boy is told how to track an Eland and how the Eland will fall once shot with an arrow. The boy will become an adult when he kills his first large antelope, preferably an Eland. Once caught, the Eland is skinned and the fat from the animal's throat and collarbone is made into a broth. In the girls' puberty rituals, a young girl is isolated in her hut at her first menstruation. The women of the tribe perform the Eland Bull Dance where they imitate the mating behaviour of the Eland cows.

A man will play the part of the Eland bull, usually with horns on his head. This ritual will keep the girl beautiful, free from hunger and thirst and peaceful. As part of the marriage ritual, the man gives the fat from the Elands' heart to the girls' parents. At a later stage, the girl is anointed with Eland fat. In the trance dance, the Eland is considered the most potent of all animals, and the shamans aspire to possess Eland potency.

The San believed that the Eland was /Kaggen's favourite animal. San people have vast oral traditions, and many of their tales include stories about the gods that serve to educate listeners about what is considered moral San behaviour.

Traditionally, bushman women spent 3-4 days a week gathering veldkost (wild plants), often going out in groups to search for edible or medicinal plants. Furthermore, before the advent of trade with Bantu or white settlers, all tools, construction material, weapons or clothes were made of plants or animal products.

About 400-500 local plants and their uses were known to bushmen, along with the places where they grew – not only providing a balanced nutrition, but also moisture from roots even in time of drought. Plants were used in ways similar to western phytomedicine to treat wounds and heal illnesses; other plants where rather part of healing ceremonies in which a healer would burn plants to make rain, trance to heal an ailment, or perform a charm to bring fertility. The range of ailments treated included wounds including snake bites, colds, stomach ache, tooth ache or headache, or diarrhea but also infections like malaria, tuberculosis, or syphilis. One bushman plant, Hoodia gordonii, even made the worldwide news since it was patented by a pharma company as a diet support due to its traditional bushman usage to suppress appetite and hunger – a law case against “bio piracy” ensued, with the parties settling to royalties being paid to bushmen organisations.

The bushmen’s diet and relaxed lifestyle have prevented most of the stress-related diseases of the western world. Bushmen health, in general, is not good though: 50% of children die before the age of 15; 20% die within their first year (mostly of gastrointestinal infections). Average life expectancy is about 45-50 years; respiratory infections and malaria are the major reasons for death in adults. Only 10% become older than 60 years.

Amongst the Bushman or San, birth is not generally a big issue. They don't really prepare and or go to a hospital like modern man. It is claimed that a Bushman women who is about to give birth will simply go behind a bush and "squeeze out" the baby. There is also some claims that they prepare a medicine from devils claw (Harpagophytum spp.), have the baby, and is back in her daily routine within a hour. In reality she is likely to take her mom or an elder aunt along, for comfort and help. The book "Shadow Bird" by Willemien le Roux, describes a Bushman birth with complications, and the old woman that was called to help, so it doesn't always go as easy as it is supposed to.

After the birth a Bushman child will receive much love and attention from his parents and other adults and even older children. Their love of children, both their own and that of other people, is one of the most noticeable things about the Bushman.

If a child is born under very severe drought conditions, when the fertility of the Bushman women are in any case low, perhaps to precvent such an occurrence. The mother will quietly relieve the just born baby of severe and certain future suffering by ending its life. This is most likely to happen in lean years, if she is still suckling another child and will obviously not be able to feed both of the children. This is accepted behaviour, and born out of necessity and not malice or any other consideration. It stems from the simple realiy of live in a harsh climate, and the realisation that the life of the child that a lot has already been invested in, and that might be put at risk by tender feelings for a new-born that are in any case likely to die soon, are not likely to have a good outcome.

Death is a very natural thing to the Bushmen. If some-ones dies at a specific camp, the clan will move away and never camp at that spot again. Bushmen will never knowingly cross the place where some-one has been buried. If they have to pass near such a place, they will throw a pebble on the grave and mutter under their breath, to the spirits to ensure good luck. They never step on a grave and believe that the spirit remains active on that spot above ground, and they don't want to offend it.

Amoing most Bushmen, a wedding is a private event between the Bridegroom and the Bride. Only in exceptional cases may a guest be invited, but there is no celebration or other ritual as we understand it, only a private "ceremony" or agreement between the two people involved.

The Bushmen don't have initiaion ceremonies. There is some dancing and cleansing ceremony after a maiden has shed her first menstrual blood. Boys are not considered men untill they have killed their first large and dangerous animal. Thereafter they are are treated as full members of the clan or tribe.

Of prime importance in all San groups is a ritual dance that serves to heal the group. The great 'medicine or healing dance' and the rain dance were rituals in which everyone participated. During these dances, the women usually sat around a central fire as they sang and clapped their hands. The men then first danced around the women in a clockwise direction and then vice versa. As the dance increased in intensity, the dancers reached trance-like, altered, states of consciousness and were transported into the spirit realm where they could plead for the souls of the sick.

These trance dances are depicted in the rock art left behind by the San. The shamanic figures are often painted in strange 'bending forward' postures. Shamans or 'medicine men' explained later that they adopted this posture during their trance dances because they experienced a great deal of pain when the 'potency' started boiling in their stomachs and their stomach muscles started contracting. They also often experienced spontaneous nosebleeds at this time. These nosebleeds are depicted in the many rock paintings of trance dances. As other groups invaded the territory of the San and influenced their way of life, the pictures of soldiers, wagons and horses served to record historical events.

The Kalahari San held similar beliefs and revered a greater and a lesser god, the first associated with life and the rising sun, and the latter with illness and death. The shamans, who went into trances and altered states of existence during ritual dances, thus acquired access to the lesser god who caused illness. Birth, death, gender, rain and weather were all believed to have supernatural significance, for example, people acquired good or bad rain-bringing abilities at birth and this ability was reactivated when the person died.

Another shared belief was the fact that, when the world was first created, animals and people were indistinguishable. People had not yet acquired manners and culture and only after the second creation, were they separated from the animals and educated in a separate social code. Most San believed that upon death, the soul went back to the great god's house in the sky. Dead people could, however, still influence the living and, when a medicine man died, the people were very concerned lest his spirit become a danger to the living.

Creation of the first Bushmen. As the Bushmen lived in a very dry area, water to them have a very magical power that could revive them. In the legend of creation Mantis appears and the entire world is still covered by water. A bee (a symbol of wisdom) carries Mantis over the turbulent waters of the ocean. The bee however, became very tired and flew lower and lower. He searched for solid land to make his decent to but he only grew more and more tired. But then he saw a flower drifting on the water. He laid Mantis down in the flower and within in him the seed of the first human. The bee drowned but when the sun came up Mantis awoke and from the seed the bee had left the first human was born.

Mantis and his family. The bushmen don't regard the Mantis as god but rather a superbeing. They are not the only civilization who has this belief and other African tribes do see it as a God. Even the Greeks believed it had divine and magical powers. Mantis is a Greek word meaning divine, or soothsayer. All over the world many legends is told about this magical creature. To the Bushmen however he is a "dream Bushman". He is very human. Many paintings of the bushmen figure a Bushman with the head of a Mantis. Mantis also has a big family. His wife is Dassie (rock hyrax). His son is also a Mantis and he also has an adopted daughter, Porcupine. Her real father is the evil monster called the All-Devourer who she is too afraid of. Porcupine is married to a creature that is part of the rainbow, called Kwammanga. They have two sons, Mongoose or Ichneumon and then Kwammanga, after his dad. Mantis also has a sister, Blue Crane that he loves very much

The Baboons. At a time long ago the baboons were little people like the Bushmen, but they were very mischievous. They loved making trouble. On a day Cagn sent his con Cogaz to go and look for sticks they could use in making bows. When the little people saw him they started dancing around the boy shouting: "Your father thinks he is clever and wants to make bows to kill us, now we will kill you!" They did as they said and Cogaz's body was hung in a tree. The little people danced again and sang: "Cagn thinks he is clever!" Then Cagn awoke from his sleep. He had a feeling that something was wrong so he asked hi wife Coti to bring him his charms. He thought and thought. Then it came to him. He realized what the little people did to his son. He immediately went in search of his son. When the little people saw him coming they started singing an other song. A little girl sitting nearby told Cagn that they were singing something else before he came. He ordered them to sing what the girl heard before. When he heard this he ordered them to stay where they are until he returns. He returned with a basket full of pegs. As they danced he drove a peg in each of their backsides. They fled to the mountains because they now had tails and they started living with animals. Cagn then climbed into the tree and used his magic to resurrect his son.

How Mantis stole fire from Ostrich. Mantis also gave the Bushmen fire. Before this people ate their food like all the other predators, raw. They also had no light at night and were surrounded by darkness. Mantis noticed that Ostrich's food always smelt very good and decided to observe what he did to his food. As he crept close one day he saw Ostrich take some fire from beneath his wing and dip his food in it. After eating he would tuck back the fire under his wing. Mantis knew Ostrich would not give him the fire so he planned a trick on Ostrich to steal the fire from him. One day he called Ostrich and showed him a tree carrying delicious plums. As Ostrich started to eat Mantis shouted at him that the best ones were at that top. Ostrich jumped higher and higher and as soon as he opened his wings Mantis stole the fire from him and ran off. Ostrich was very ashamed of this and since that day kept his wings pressed to his sides and will never fly.

The Rainbow. Rain was once a beautiful woman who lived in the sky. She wore a rainbow around her waist and she was married to the creator of the earth. They had three daughters. When the eldest daughter grew up she asked her mother to go down to earth. Her mother gave her permission but as soon as se went down she got married to a hunter. While she was gone Rain had another child. This time a boy which she called Son-eib. When he was old enough his sisters asked Rain if they could all go down to see the world. In fear of losing them all Rain didn't want them to go. But then a friend Wolf who liked the two daughters said he would accompany them down and look after them. The father believed this wicked beast and gave his permission.

As soon as they got to earth they went to a village. A woman in the village saw Son-eib and he looked very familiar to her. She offered them food and Wolf accepted this. They all ate of this food except Son-eib as Wolf told everybody that he is not a person but merely a thing. Son-eib turned away and went to sit in the grass, all by himself. While sitting there he caught a little red bird. He concealed it under his coat.

That night the woman offered them shelter in her house. But once again Wolf did not allow the boy to sleep inside the house and said that Son-eib should sleep in the small hut outside. While everybody was sleeping Wolf went and fetched all the bad people in the village. They set fire to the hut killing poor Son-eib. However, the little bird managed to escape. It flew up into the sky and went straight to Rain, the boy's mother.

As soon as it arrived it told Rain of what has happened. Rain told her husband and they were furious. A little while later the people of the village saw a great storm approaching them fast and around its waist was a rainbow. Lightning started to flash striking all around them. Only Wolf and his fellow bad people were hit and killed. Then a mighty voice came from the sky with the words: "Don't kill the children of the sky!"

Ever since this all Bushmen are afraid of the rainbow. When the bushmen see a rainbow they would hit on sticks and shout for it to go away!

The sun, moon and the stars. One of the stories of the sun says that he is a man from whose armpits shine the rays of light. He did not want to share his light with all the people so he stayed in his hut. The first Busman ordered hi children to throw him into the sky. They threw him up and this is where he still shines from today. In the night he is very cold so he draws his blanket over him. This blanket is very old and has lots of little holes in it. This is the stars we see at night.

Another tale tells of a young woman who waits for the hunters to return every night. When it grows dark she throws up a handful of white ash. This becomes the Milky-way that guide the hunters home.

The moon is believed to be the old shoe of Mantis. He placed it in the air to guide him at night. The sun is very jealous of the moon when it is at its full brightness. The sun uses its sharp rays to cut of pieces of the moon bit by bit until there is almost nothing left of the moon. The moon begs the sun to stop and then he always goes away. Soon after the moon starts growing again until it is full and the whole process repeats itself.

Today, the San suffer from a perception that their lifestyle is 'primitive' and that they need to be made to live like the majority cattle-herding tribes. Specific problems vary according to where they live. In South Africa, for example, the !Khomani now have most of their land rights recognised, but many other San tribes have no land rights at all. Few modern San are able to continue as hunter-gatherers, and most live at the very bottom of the social scale, in unacceptable conditions of poverty, leading to alcoholism, violence, prostitution, disease and despair.

The last of the hunter-gatherers were forcibly evicted from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve as recently as April 2002, by the Botswana government to make way for diamond mines. A court case is currently in existence to help the San claim their land.

The official reason was to provide them with services such as schools and medical services, and to bring them into modern society. In fact, few of these services have materialized, and the San have been confined to bleak encampments in a hostile environment. The San are a friendly, creative, and peaceful people, who never developed any weapons of war, and have lived in harmony with their natural environment for at least 20 000 years. Properly restored to their ancestral lands, and reintegrated into the game reserves of southern Africa, San communities could become self-sustaining.

The hardiness of the San allowed them to survive their changed fortunes and the harsh conditions of the Kalahari Desert in which they are now mostly concentrated. Today, the small group that remains has adopted many strategies for political, economic and social survival.

The San retain many of their ancient practices but have made certain compromises to modern living. The westernised myths regarding the San have caused considerable damage. They portray the San as simple, childlike people without a problem in the world. This could not be further from the truth.

Due to absorption but mostly extinction, the San may soon cease to exist as a separate people. Unfortunately, they may soon only be viewed in national museums. Their traditions, beliefs and culture may soon only be found in historical journals.

A fairly large community of bushmen, the Ju/'hoansi, today live on both sides of the border between Namibia and Botswana, named Bushmanland. This group has been studied, filmed and assisted by Western scholars since 1951. The academic studies continue to this day and they are under the general guidance of the "Ju/wa Bushman Development Foundation" which is essentially a group of concerned individuals and academia. In 1991, with the formation of the "Nyae Nyae Farmers Cooperative" and with representation and guidance from the "Ju/wa Bushman Development Foundation", they managed to secure land rights within Bushmanland.

They are still permitted to hunt within the boundaries, despite being a game conservation area, as long as they use traditional methods. It means no firearms, dogs, vehicles or horses, rules that are occasionally broken and usually results in a prison term for the offenders.

One of the biggest problems is alcoholism, brought about mainly by military stationed in the local town of Tsumkwe bringing alcohol into the region despite a government ban on bringing in spirits. Having virtually no tolerance of alcohol, there was a massive increase in drunkenness, alcoholism and crime with a general decline in family structures and community well-being.

The Gana (G//ana) and Gwi (G/wi) tribes in Botswana's Central Kalahari Game Reserve are among the most persecuted. Far from recognising their ownership rights over the land they have lived on for thousands of years, the Botswana government has in fact forced almost all of them off it. In the early 1980s, diamonds were discovered in the reserve. Soon after, government ministers went into the reserve to tell the Bushmen living there that they would have to leave because of the diamond finds.

In three big clearances, in 1997, 2002 and 2005, virtually all the Bushmen were forced out. Their homes were dismantled, their school and health post were closed, their water supply was destroyed and the people were threatened and trucked away.

Almost all were forced out by these tactics, but a large number have since returned, with many more desperate to do so. They now live in resettlement camps outside the reserve. Rarely able to hunt, and arrested and beaten when they do, they are dependent on government handouts. They are now gripped by alcoholism, boredom, depression, and illnesses such as TB and HIV/AIDS.

Although the Bushmen won the right in court to go back to their lands in 2006, the government has done everything it can to make their return impossible. Since then the government has arrested more than 50 Bushmen for hunting to feed their families, and banned the Bushmen from using their water borehole.

Hundreds still languish in resettlement camps, unable or scared to return home. Unless they can return to their ancestral lands, their unique societies and way of life will be destroyed, and many of them will die.

Bushmen around the town of Ghanzi had served as cattle herders to Afrikaans farmers since early 20th century. They worked in largely unfenced ranges. There were still some benefits for the Bushmen as game was still fairly abundant, while getting the spin-off benefits of some milk, some money and even the occasional cow that died naturally.

All this changed significantly, courtesy of the European Common Market, who in their wisdom offered a very high price for Botswana's beef as long as they instituted major disease control measures to eliminate foot & mouth, anthrax and a few other endemic ailments. This resulted in an extensive game control fencing operation to separate the cattle from the “disease ridden wildlife”. Unfenced ranges with moderate levels of wildlife became fenced in lands with a catastrophic drop in game numbers due to a cut of the herds’ migration routes to cope with drought. The Common Market (later the European Economic Community) were happy and paid the massively inflated prices, while subsistence game hunting became meaningless. The cattle monoculture further destroyed the bushmen’s plant resources, severely impacting their traditional hunter and gatherer lifestyle.

These Bushmen from the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park (now the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park) region were ejected from the Reserve between 1931, upon its formation, & 1973 when the last were finally evicted. They had initially during this period been allowed limited assess and work within the reserve but were finally removed by the management. Despite many attempts to get access to their traditional hunting areas, entry was denied on the basis that they would become a problem begging from tourists. This was despite the valid argument that the large southwestern region requested was off limits to visitors to the reserve and therefore should not present any difficulties. They remained a small impoverished group largely integrating themselves within the mixed coloured communities that developed along the fringes of the Reserve, working where possible for local farmers.

A group of bushmen still partially adhering to their traditional life and family structure, under their leader Dawid Kruiper were finally successful in 1999 when 40 000 hectares of land next to the Kgalagadi Park was purchased by the government from local farmers and given back to the Khomani community. In 2001 it was agreed that an additional 25 000 hectares of the Kalahari Gemsbok park was to be returned to them for managed utilisation but not for residence. Tension between the traditional and westernised bushmen led to various power struggles, but some of the bushmen continue to occasionally hunt and gather. Furthermore, the community-owned !Xaus luxury lodge recently opened in the Southwestern-most part of Kgalagadi Park.

Sources: