The Luhya (also known as Abaluyia or Luyia) are a group of 19 distinct Bantu tribes in Kenya that lack a common origin and were politically united in the mid 20th century. They number 6,823,842 people according to the 2019 census, being about 14.35% of Kenya's total population of 47.6 million, and are the second-largest ethnic group in Kenya.

Luhya refers to both the 19 Luhya tribes and their respective languages collectively called Luhya languages and the current King is Peter Nantinda Mumia. There are 19 (and by other accounts, 20, when the Suba are included) tribes that make up the Luhya. Each has a distinct dialect. The word Luhya or Luyia in some of the dialects means "the north", and Abaluhya (Abaluyia) thus means "people from the north". Other translations are "those of the same hearth."

The seventeen tribes are the:

They are closely related to the Masaba (or Gisu), whose language is mutually intelligible with Luhya. The Bukusu and the Maragoli are the two largest Luhya tribes.

The principal traditional settlement area of the Luhya is in what was formerly the Western province of Kenya. A substantial number of them permanently settled in the Kitale and Kapsabet areas of the former Rift Valley province. Western Kenya is one of the most densely populated parts of Kenya. Migration to their present Luhyaland (a term of endearment referring to the Luhya's primary place of settlement in Kenya after the Bantu expansion) dates back to as early as the 1450s.

Immigrants into present-day Luhyaland trace their ancestry with several Bantu groups and Cushitic groups, as well as peoples like the Kalenjin, Luo, and Maasai. By 1850, migration into Luhyaland was largely complete, and only minor internal movements occurred after that due to disease, droughts, domestic conflicts and the effects of British colonialism.

1. The Bukusu speak Lubukusu and occupy Bungoma and Mount Elgon districts. The clans of the Bukusu include the Bamutilu,Babuya,Batura, Bamalaba, Bamwale, Bakikayi, Basirikwa, Baechale, Baechalo, Bakibeti, Bakhisa, Bamwayi Bamwaya, Bang'oma, Basakali, Bakiabi, Baliuli, Bamuki, Bakhona, Bakoi, Bameme, Basombi, Bakwangwa, Babutu (descendants of Mubutu also found in Congo), Bakhoone, Baengele (originally Banyala), Balonja, Batukwika, Baboya, Baala, Balako, Basaba, Babuya, Barefu, Bamusomi, Batecho, Baafu, Babichachi, Bamula, Balunda, Babulo, Bafumo, Bayemba, Baemba, Bayaya, Baleyi, Baembo, Bamukongi, Babeti, Baunga, Bakuta, Balisa, Balukulu, Balwonja, Bamalicha, Bamukoya, Bamuna, Bamutiru, Bayonga, Bamang'ali, Basefu, Basekese, Basenya, Basime, Basimisi, Basibanjo, Basonge, Batakhwe, Batecho, Bachemayi, Bachemwile, Bauma, Baumbu, Bakhoma, Bakhonjo, Bakhwami, Bakhulaluwa, Baundo, Bachemuluku, Bafisi, Bakobolo, Bamatiri, Bamakhuli, Bameywa, Bahongo, Basamo, Basang'alo, Basianaga, Basioya, Bachambayi, Bangachi, Babiya, Baande, Bakhone, Bakimwei, Batilu, Bakhurarwa, Bakamukong'i, Baluleti, Babasaba, Bakikai, Bhakitang'a, Bhatemlani, Bhasakha, Bhatasama, Bhakiyabi, Banywaka, Banyangali, etc. For a complete list of Bukusu clans see Shadrack Amakoye Bulimo's new book Luyia Nation: Origins, Clans and Taboos

2. The Samia speak Lusamia and occupy Southern Region of Busia District (Busia county), Kenya. The clans of the Samia of include the Abatabona, Abadongo, Abakhino, Abakhulo, Abakangala, Abasonga, Ababukaki, Ababuri, Abalala,Abanyiremi, Abakweri, Abajabi, Abakhoba, Abakhwi, Abadulu,

3. The Khayo speak Lukhayo and occupy Nambale District and Matayos Division of Busia County, Kenya. Khayo clans include the Abaguuri, Abasota, Abakhabi.

4. The Marachi speak Lumarachi and occupy Butula District in Busia county. Marachi clans include Ababere, Abafofoyo, Abamuchama, Abatula, Abamurono, Abang'ayo, Ababule, Abamulembo, Abatelia, Abapwati, Abasumia, Abarano, Abasimalwa, Abakwera, Abamutu, Abamalele, Abakolwe, Ababonwe, Abamucheka, Abaliba, Ababirang'u, Abakolwe, Abade. Abasubo.The name Marachi is derived from Ng'ono Mwami's father who was called Marachi son of Musebe, the son of Sirikwa.So all the Marachi clans owed their allegiance to Ng'ono Mwami from whose lineage of Ababere clan they were founded. The name Marachi was given further impetus by the war-like lifestyle of the descendants of Ng'ono who ruthlessly fought off the Luo expansion of the Jok Omollo a Nilotic group that sought to control the Nzoia and Sio Rivers in the area and the fishing grounds around the gulf of Erukala and Ebusijo-modern Port Victoria and Sio Port respectively.

5. The Nyala speak Lunyala and occupy Busia District. Other Nyala (Abanyala ba Kakamega) occupy the north western part of Kakamega District. The Banyala of Kakamega are said to have migrated from Busia with a leader known as Mukhamba. They speak the same dialect as the Banyala of Busia, save for minor differences in pronunciation. The Abanyala ba Kakamega are also known as Abanyala ba Ndombi. They reside in Navakholo Division North of Kakamega forest. Their one-time powerful colonial chief was Ndombi wa Namusia. Chief Ndombi was succeeded by his son, Andrea.

Andrea was succeeded by Paulo Udoto, Mukopi, Wanjala, Barasa Ongeti, Matayo Oyalo and Muterwa in that order.

The clans of the Banyala include Abahafu, Ababenge, Abachimba, Abadavani, Abaengere, Abakangala, Abakhubichi, Abakoye, Abakwangwachi, Abalanda, Abalecha, Abalindo, Abamani, Abalindavyoki, Abamisoho, Abamuchuu, Abamugi, Abamulembo, Abamwaya, Abanyekera, Abaokho, Abasaacha, Abasakwa, Abasaya, Abasenya, Abasia, Abasiloli, Abasonge (also found among Kabras), Abasumba, Abasuu, Abatecho (also found among Bukusu), Abaucha, Abauma, Abaumwo, Abacharia, Abayaya, Abayirifuma (also found among Tachoni), Abayisa, Abayundo and Abasiondo, Abachende.

The Banyala do not intermarry with someone from the same clan.

6. The Kabras speak Lukabarasi and occupy the northern part of Kakamega district. The Kabras were originally Banyala. They reside principally in Malava, in Kabras Division of Kakamega district. The Kabras (or Kabarasi, Kavalasi and Kabalasi) are sandwiched by the Isukha, Banyala and the Tachoni.

The name "Kabras" comes from Avalasi which means 'Warriors' or 'Mighty Hunters.' They were fierce warriors who fought with the neighbouring Nandi for cattle and were known to be fearless. This explains why they are generally fewer in number compared to other Luhya tribes such as the Maragoli and Bukusu.

They claim to be descendants of Nangwiro associated with the Biblical Nimrod. The Kabras dialect sounds like the Tachoni dialect. Kabras clans include the Abamutama, Basonje, Abakhusia, Bamachina, Abashu, Abamutsembi, Baluu, Batobo, Bachetsi and Bamakangala. They were named after the heads of the families.

The Kabras were under the rulership of Nabongo Mumia of the Wanga and were represented by an elder in his Council of Elders. The last known elder was Soita Libukana Samaramarami of Lwichi village, Central Kabras, near Chegulo market. When the Quaker missionaries spread to Kabras they established the Friends Church (Quakers) through a missionary by the name of Arthur Chilson, who had started the church in Kaimosi, in Tiriki. He earned a local name, Shikanga, and his children learned to speak Kabras as they lived and interacted with the local children.

7. The Tsotso speak Olutsotso and occupy the western part of Kakamega district. Tsotso clans include the Abangonya, Abashisiru, Abamweche, Abashibo,

8. The Idakho speak Lwidakho and occupy the southern part of Kakamega district. Their clans include the Abashimuli, Abashikulu, Abamasaba, Abashiangala, Abamusali, Abangolori, Abamahani, Abamuhali.

9. The Isukha speak Lwisukha and occupy the eastern part of Kakamega district. Isukha clans include the Abarimbuli, Abasaka- Ia, Abamakhaya, Abitsende, Abamironje, Abayokho, Abakusi, Abamahalia, Abimalia, Abasuiwa, Abatsunga, Abichina, Abashilukha, Bakhumbwa, Baruli, Abatura, Abashimutu, Abashitaho, Abakhulunya, Abasiritsa, Abakhaywa, Abasaiwa, Abakhonyi, Abatecheri, Abayonga, Abakondi, Abaterema, and Abasikhobu.

10. The Maragoli speak Lulogooli and occupy Vihiga district. Maragoli clans include Avamumbaya, Avamuzuzu, Avasaali, Avakizungu, Avavurugi, Avakirima, Avamaabi, Avanoondi, Avalogovo, Avagonda, Avamutembe, Avasweta, Avamageza, Avagizenbwa, Avaliero, Avasaniaga, Avakebembe, Avayonga, Avagamuguywa, Avasaki, Avamasingira, Avamaseero, Avasanga, Avagitsunda.

11. The Nyole speak Olunyole and occupy Bunyore in Vihiga district. Nyole clans include Abakanga, Abayangu, Abasiekwe, Abatongoi, Abasikhale, Aberranyi, Abasakami, Abamuli, Abasubi (Abasyubi), Abasiralo, Abalonga, Abasiratsi. Abamang’ali, Abanangwe, Abasiloli, Ab’bayi, Abakhaya, Abamukunzi and Abamutete.

12. The Tiriki speak Ludiliji and occupy Tiriki in Vihiga district. Tiriki clans include Balukhoba, Bajisinde, Baumbo, Bashisungu, Bamabi, Bamiluha, Balukhombe, Badura, Bamuli, Barimuli, Baguga, Basianiga and Basuba.

13. The Wanga speak Oluwanga and occupy Mumias and Matungu Districts. The 22 Wanga clans are Abashitsetse, Abakolwe, Abaleka, Abachero, Abashikawa, Abamurono, Abashieni, Abamwima, Abamuniafu, Abambatsa, Abashibe, Ababere, Abamwende, Abakhami, Abakulubi, Abang’ale, Ababonwe, Abatsoye, Abalibo, Abang’ayo, Ababule and Abamulembwa.

14. The Marama speak Lumarama and occupy Butere district. Marama clans include Abamukhula, Abatere, Abashirotsa, Abatsotse, Aberecheya, Abamumbia, Abakhuli, Abakokho, Abakara, Abamatundu, Abamani, Abashieni, Abanyukhu, Abashikalie, Abashitsaha, Abacheya, etc.

15. The Kisa speak Olushisa and occupy Khwisero district. Kisa clans include Ababoli, Abakambuli, Abachero, abalakayi, Abakhobole, Abakwabi, Abamurono, Abamanyulia, Abaruli, Abashirandu, Abamatundu, Abashirotsa, Abalukulu etc.

16. The Tachoni speak Lutachoni and occupy Lugari, Bungoma and Malava districts. Tachoni clans include Abachambai, Abamarakalu, Abasang'alo, Abangachi, Abasioya, Abaviya, Abatecho, Abaengele. The Saniaga clan found among the Maragoli in Kenya and the Saniak in Tanzania are said to have originally been Tachoni.

Luluyia-speaking groups have occupied the same East African region for up to 500 years; they displaced long-established foraging and herding peoples. The Abaluyia subnations, most of which probably originated from central Africa, were originally clans with diverse historical origins that grew large and then split into subclans. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were characterized by widespread warfare between Abaluyia subnations and neighboring ethnic groups, especially the Buganda, Luo, Nandi, Maasai, and Iteso. The Bagisu, Bakhayo, Bukusu, Banyala, Batsotso, Kabras, Nyole, Marachi, Marama, Samia, and Tachoni constructed fortressed settlements during this period. These were walled with thorns and surrounded by moats.

During the colonial period (1895-1963), the British, whose goal was to pacify the area and facilitate the completion of the Uganda Railway, made several unsuccessful attempts to unite politically the Luluyia-speaking subnations. In 1895 the Bukusu waged an unsuccessful war of resistance, the Chetambe War, against the British. The first train reached Kisumu in 1901. The Abaluyia region was split in two in 1902, when the British established the current boundary between Kenya and Uganda. As a result, the subnations in Kenya and Uganda have different colonial histories and different political economies. In 1909, in a futile attempt to unite the subnations, the British anointed Nobongo Mumia of the Wanga "kingdom" the "supreme" chief. The Abaluyia, however, never had a single paramount chief prior to British colonial rule. The Ugandan Nyole were dominated by the Baganda; various clan leaders in Kenya aligned themselves with or resisted the British. The Kenyan Abaluyia did not develop a unified ethnic identity until the 1930s, and the Ugandan Luluyia speakers have never had a single ethnic identity.

The Friends African Mission, the Mill Hill Mission, the Church of God, and the Church Missionary Society (Anglican) were all established in the region between 1902 and 1906; mission schools were established shortly thereafter. A brief gold rush (1929-1931) was followed by land confiscation and alienation. Today nearly all Abaluyia are Christians, although some Abaluyia—especially around Mumias town—practice Islam. Universal primary education has been achieved in much of western Kenya.

Precolonial Abaluyia villages were loosely organized around single localized lineages ( enyumba; pl. tsinyumba ). Abaluyia homesteads consisted of circular compounds surrounded by euphorbias, thorns, or clay walls. Structures within the compounds followed a prescribed layout, although there were variations. Houses were circular with thatched roofs. The first wife's house was directly opposite the gate, with the houses of junior wives organized to the left and right, according to seniority. The married sons' houses were near the gate and were arranged according to birth order. Because unmarried children who had reached puberty were not permitted to sleep under the same roof as their parents, unmarried sons slept in special houses called chisimba (sing, esimba ). Girls, and sometimes younger boys, slept with classificatory grandmothers in girls' houses ( ekogono or eshibinze ). The compound usually had one or more elevated granaries, and animals were often kept in separate structures. Nowadays settlements are organized more like neighborhoods. Mud houses are usually square and often roofed with iron sheets. Modern block houses with tile roofs line the major roads. Compounds are often crowded and may be laid out less formally. They are surrounded by euphorbias, shrubs, rows of trees, or fences. In some places, girls' houses no longer exist: girls sleep in their mothers' kitchens, but older boys continue to sleep in separate dwellings. Granaries are still common in the Bukusu area but are rare in Maragoli and Banyore.

Subsistence and Commercial Activities. The Abaluyia are now primarily farmers who keep cattle, but in precolonial times men hunted, and animal husbandry was even more important. The Banyala and the Samia were known for their expertise in fishing, and quail and insects were eaten throughout the region. Finger millet, sorghum, sesame, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, yams, beans, and bananas were the most important crops in precolonial times. Nowadays the main crop is maize intercropped with beans; millet and sorghum are less common. In addition to the traditional crops, other important contemporary crops include green beans, red beans, bananas, groundnuts (peanuts), sukuma wiki (kale), cabbages, potatoes, and cassava. The major cash crops are tea, coffee, sugarcane, cotton, and sunflower seeds. Farms are tilled entirely with iron hoes in the hillier, more densely populated areas, whereas hoes are commonly used with ox-drawn plows and tractors in the northern and western regions. Cattle (zebu, mixed, and grade), goats, sheep, chickens, ducks, and turkeys are common.

Industrial Arts. Formerly, the important crafts were blacksmithing, pottery, basketry, woodworking (particularly, the manufacture of drums), and weaving. Blacksmtthing had been passed down patrilineally in some clans. The Samia (especially the Abang'aale clan) were particularly well known for blacksmithing and mining of iron ore. Manufacture of pottery was more often a woman's than a man's task—although Bukusu women of childbearing age could not quarry clay. Pots, which were usually traded and owned by women, were considered utilitarian. There was not much specialization in the manufacture of everyday wood tools (e.g., hoe handles), but specialists still make drums, lyres, stools, and wood carvings.

Trade. The subnations of the Abaluyia traded among one another during the precolonial era. Iron hoes, spear points, and ivory, for example, could be traded for grains or animals. Precolonial trade covered a distance of no more than 72 kilometers, but there were three precolonial markets where Luo, Nandi, and Abaluyia came together to trade baskets, wooden tools, quail, and various foodstuffs for cattle, fish, tobacco, and so forth. During the colonial era, various weekly regional and local market centers developed, where local and European goods could be bought or bartered. Wagner counted sixty-four recognized markets in 1937. By 1990, in addition to dozens of rural, market, and local trading centers, there were at least ten urban centers in Western Province, Kenya, where one could buy everything from Diet Coke to Michael Jackson tapes.

Division of Labor. In precolonial times, hunting and warfare were important men's work. Horticulture was mainly women's work. Men cleared fields, but women usually prepared soil, planted, weeded, and harvested. Only men planted trees, although women cared for them. Large animals were the domain of men and unmarried boys. Traditionally, the men milked the cattle in most of the subnations, but nowadays women often do it. Women owned and cared for poultry. Both women and men were involved in marketing: the women sold pots, products grown in kitchen gardens, dried fish, fruits, and grains bought from farmers in other regions. Only men took animals to market. House building has many stages, each with a division of labor; however, women generally repaired walls and floors, whereas men prepared thatching materials. Children contributed to subsistence: girls mainly in the home and fields, boys mainly with the herds. Boys and girls helped out with other tasks, such as tending younger children, gathering wood, and fetching water. Girls helped their mothers in selling. Nowadays men's and women's roles are more varied. Although the sexual division of labor at home has not changed much, both men and women have a broader range of occupational opportunities. Schoolteacher, agricultural-extension worker, and sugar-factory worker are common occupations of rural Abaluyia. The sexual division of labor in agriculture has changed somewhat as agriculture has intensified. Modern Abaluyia children usually attend school and are less available to perform chores.

Land Tenure. Traditionally, land was inherited patrilineally. Among the Kenyan Abaluyia, families owned land, and this land was referred to as the omulimi gwa guga (lands of the grandfather). A man apportioned his land to sons as they married but could not alienate the omulimi gwa guga. Women had use rights on their husbands' farms but could not inherit land. Mothers could, however, hold land in trust for sons. When his mother died, the last-born son would inherit the land she farmed. Communal lands, such as surplus lands or those used for grazing, were under the control of the clan and administered by the luguru (headman). Women are permitted to inherit land in contemporary Kenya but more often acquire land by purchasing it themselves. Communal grazing lands are now rare because of population pressure. Most land is registered, and buying and selling of land are individual affairs. Land disputes are handled in courts or in sublocation meetings convened by assistant chiefs.

Kin Groups and Descent. The exogamous patrilineal clan ( oluyia ) is the fundamental unit of Abaluyia social organization. Clans may also have several exogamous subclans. There were at least 750 Abaluyia clans by the mid-twentieth century. Each clan has an animal, plant, or bird totem, as well as an ancestor for whom the clan is usually named.

Kinship Terminology. The Abaluyia use an Iroquoian system that incorporates classificatory kinship terminology. Grandparents and grandchildren are called by the same kin terms— guga for grandfathers, grandsons, and great-grandsons, guku for grandmothers, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters. Distinctions are made for the father's sister ( senje ) and mother's brother ( khotsa ), but clan relatives of the same generation (e.g., women and female in-laws) are called by the same term (in this case, mama ). Cousins are addressed by sibling terms, but, in some places, cross cousins are distinguished in reference.

Marriage. Traditional Abaluyia marriage is patrilocal. Polygyny rates vary among the subnations, and bride-wealth, consisting of animals and money, is usually exchanged. Many types of exchange occurred during the marriage process, and male elders conducted the negotiations. Wives were chosen for their good character and the ability to work hard. Men were also chosen for these qualities, as well as soberness and ability to pay bride-wealth. After marriage, co-wives usually had separate dwellings but would often cook together. New wives were not permitted to cook in their own houses until their own cooking stones were set up in a brief ceremony. This was often after the birth of one or several children. Childlessness was usually blamed on the woman. In some subnations, a woman whose husband died lived in a state of ritual impurity until she was inherited by the dead husband's brother. Divorce may or may not have involved return of bride-wealth cattle. In the case of divorce or serious witchcraft accusations, the woman could return to her natal home without her children, who remained with their fathers.

Abaluyia women in contemporary Kenya choose among a variety of marriage options, including the traditional bride-wealth system, Christian marriage with or without bride-wealth, elopement, and single parenthood. Women with more education may command a higher bride-wealth. Bride-wealth in Bungoma remains stable, but in Maragoli and some other regions, bride-wealth may be declining or disappearing. Domestic Unit. A married man heads one or more households. A typical household consists of a husband, a wife, and their children. Other family members may join these households, including the wife's sisters, the husband's other children, and foster children. Since mature relatives of adjacent generations do not sleep in the same house, grandmothers and older children often occupy adjacent houses; however, all usually eat from the same pot. These rules have not changed much, although many rural households are now headed by women because of long-term male wage-labor migration. Inheritance. Land is inherited patrilineally (see "Land Tenure").

Socialization. Abaluyia communities are characterized by a high degree of sibling involvement in caretaking, under the general supervision of the mothers and grandmothers in the homestead. Although mothers play a primary role in child rearing, small children and infants may be left with older siblings while their mothers do other work. Although fathers play a minimal role, they are often the ones who take children for medical care. Grandparents and grandchildren have close relationships. Until the mid-to late twentieth century, girls learned about marriage and sexuality from their grandmothers. In the Abaluyia subnations that circumcise, boys are admonished by male elders and taught to endure the pain of circumcision without flinching, a sign that they have the strength of character to endure other hardships they may face. Contemporary Abaluyia grandparents play an even greater role in child rearing because they are thrust more and more into foster-parent roles.

Social Organization. Although some clans were known for particular roles and strengths during the eighteenth through early-twentieth centuries, leadership has come from a variety of clans and subnations over the years. The range of social stratification among the Abaluyia extends from the landless to poor, middle-level, and rich farmers, depending upon such factors as the size of the plot owned and the number of animals kept. There is a developing class system but no formal hierarchy.

Political Organization. Prior to the colonial period, the highest level of political integration was the clan, and the clan headman was the most powerful figure. In some of the subnations, patron-client relationships developed between powerful clan heads and landless men who would serve as warriors. These big-men later gained power through alliances with the British, but there were no precolonial chiefs among the Abaluyia. Nevertheless, some clans and individuals were viewed as having particularly good leadership abilities. In Kenya, the traditional headman system changed in 1926 with the institution of milango headmen (usually, they were also luguru headmen), then the ulogongo system in the 1950s. Currently, villages are headed by luguru, sublocations are headed by government-hired and -paid assistant chiefs, and a paid chief leads at the location level.

Social Control. Crimes, misdeeds, land disputes, and the like were originally handled by the clan. Nowadays, in Kenya, these matters proceed initially to the headmen and assistant chiefs, who deal with local disputes at a monthly baraza (community meeting). Unresolved cases may be taken up by the location chief, district officer, or district commissioner; final recourse may be sought in the Kenyan court system.

Conflict. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Abaluyia subnations and clans often raided and warred against each other and against their non-Abaluyia neighbors (see "History and Cultural Relations"). This warfare accelerated toward the end of the nineteenth century with the arrival of the British and the introduction of firearms. Pax Britannica was achieved in 1906, but feuds and rivalries continued within clans and subclans even into the postcolonial era. The Marachi and Wanga eventually formed military alliances with the British, but others, such as the Bukusu, waged wars of resistance. Conflicts are now rare, although political events in Kenya in the 1990s have resulted in some interethnic fighting at the margins of the Abaluyia region.

Religious Beliefs. There is a sharp distinction between precolonial religious beliefs and contemporary ones. Prior to missionization, the Abaluyia believed in a High God, Were, as well as in the concept of ancestral spirits. Some said that Were lived on Mount Elgon. Ancestral spirits had power in everyday life and could cause illness and death. After 1902, the first U.S. Quaker missionaries arrived in Kaimosi and began to convert the Tiriki and Maragoli with varying success (see "History and Cultural Relations"). Other missions followed, and the schooling and wage-labor opportunities available to the converted were very attractive to the ambitious. By the 1930s, at least six Christian missions were in place in western Kenya, boasting 50,000 converts. Nowadays, worshipers of ancestral spirits are rare; nearly everyone is a Christian, Muslim, or self-described "backslider." It is important to note, however, that missionary teachings have not abolished certain traditional practices; for example, beliefs in ancestral powers are still widespread.

Religious Practitioners. Traditional practitioners included garden magicians and rain magicians. Witchcraft, sorcery, and traditional healing continue to play a role in Abaluyia communities. Both men and women can be healers or practice witchcraft. A common witchcraft accusation is that a person is a night runner—that is, he or she keeps a leopard in the house and runs naked at night rattling neighbors' doors and windows. Untimely deaths may be blamed on witchcraft and sorcery. Beliefs in poisoning or nonspecific causation of death, illness, or misfortune by witchcraft or sorcery are common. Traditional healers undergo a kind of ritual healing themselves and are indoctrinated by other healers. Healers may also have expertise with herbal medicines.

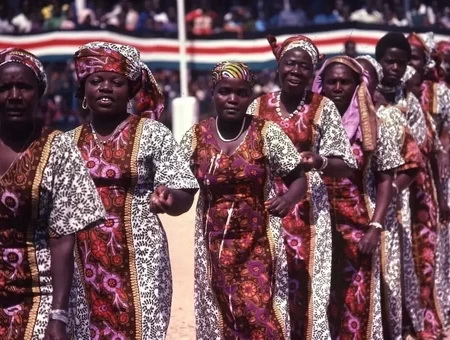

Ceremonies. Transitions from one life stage to the next are the most celebrated events. The important transitions for women are coming of age, marriage, and giving birth, whereas initiation is the most important event for men. In some subnations (Batsotso, Banyore, Kisa, Marama, and Wanga), six lower teeth were extracted in childhood; others extracted only one (Idakho, Isukha) or two (Bukusu). The extraction of teeth varied widely and was probably borrowed from neighboring ethnic groups. Men and women were often scarified at marriage, but now only the very old have any scarification. Male circumcision is important in the Bukusu, Banyore, Batsotso, Banyala of Kakamega District, Idakho, Isukha, Kabras, Kisa, Logoli, Marama, Tachoni, Tiriki, and Wanga subnations. The Gisu also circumcise. Some subnations neighboring the Luo do not circumcise, including the Bakhayo, Basonga, Gwe, Marachi, Samia and some Banyole. Circumcision ceremonies vary between subnations, although the stages usually consist of a period of preparation, the circumcision day, and a subsequent period of seclusion. The Bukusu and Tachoni have cyclical age-set systems with names that repeat about every one hundred years. Bukusu and Tachoni circumcise every two years. Some Abaluyia subnations are similar to the Logoli, who circumcise once every ten years and whose circumcision groups are named after a current event. Traditionally, boys were usually circumcised between ages 12 and 18 but could be circumcised earlier or later. A requirement of a traditional circumcision is demonstration of bravery. Even a flinch or change of expression can result in lifelong shame and disgrace. Nowadays circumcisions are done at younger ages, and boys may be circumcised in hospitals. Female circumcision was once practiced only by the Tachoni and the Bukusu, who probably adopted it from their Kalenjin neighbors.

Initiation. With the smugglers of the Marama and Saamia, male circumcision was practised. A few sub-ethnic groups practiced clitoridectomy but, even in those, it was limited to a few instances and was not as widespread as it was among the Agikuyu. The Maragoli did not practice it at all. Outlawing of the practice by the government led to its end, even though it can occur among the Tachoni.

Traditionally, circumcision was part of a period of training for adult responsibilities for the youth. Among those in Kakamega, the initiation was carried out every four or five years, depending on the clan. This resulted in various age sets notably, Kolongolo, Kananachi, Kikwameti, Kinyikeu, Nyange, Maina, and Sawa in that order.

The Abanyala in Navakholo initiate boys every other year and notably on even years. The initiates are about 8 to 13 years old, and the ceremony was followed by a period of seclusion for the initiates. On their coming out of seclusion, there would be a feast in the village, followed by a period of counselling by a group of elders.

The newly initiated youths would then build bachelor-huts for each other, where they would stay until they were old enough to become warriors. This kind of initiation is no longer practiced among the Kakamega Luhya, with the exception of the Tiriki.

Nowadays, the initiates are usually circumcised in hospital, and there is no seclusion period. On healing, a party is held for the initiate — who then usually goes back to school to continue with his studies.

Among the Bukusu, the Tachoni and (to a much lesser extent) the Nyala and the Kabras, the traditional methods of initiation persist. Circumcision is held every even year in August and December (the latter only among the Tachoni and the Kabras), and the initiates are typically 11 to 15 years old.

Arts. There are few specialized arts in the Abaluyia region. Houses are sometimes painted on the outside, especially during the Christmas season.

Medicine. Contemporary Abaluyia seek medical assistance in a variety of settings, including hospitals and clinics, and from both community health workers and traditional healers (see "Religious Practitioners").

Death and Afterlife. Death may be attributed to both natural and supernatural causes. The deceased are usually buried on their own compounds. Abaluyia funerals typically involve a period of wailing immediately after the death, a time when the body of the deceased can be viewed, and the funeral itself. During the period after the funeral, animals are slaughtered, widows' roles are considered, and some family members shave their heads. In some Abaluyia subnations, the announcement of the death of an important man or woman may have been accompanied by a cattle drive. Funeral celebrations can involve great expense and last for several days and nights, often accompanied by dancing and drums. Widows are ritually unclean for a period after the death of their spouses and are subject to a number of prohibitions. Traditionally, the widow sometimes wore her dead husband's clothes until she was inherited by his brother. Musambwa were believed to have an active role in the world of the living, and, in former times, people would call upon them to change their fortunes. Illness and death were attributed to angry musambwa.

Luhya culture is comparable to most Bantu cultural practices. Polygamy was a common practice in the past but today, it is only practiced by few people, usually, if the man marries under traditional African law or Muslim law. Civil marriages (conducted by government authorities) and Christian marriages preclude the possibility of polygamy.

About 10 to 15 families traditionally made up a village, headed by a village headman (Omukasa). Oweliguru is a post-colonial title for a village leader coined from the English word "Crew." Within a family, the man of the home was the ultimate authority, followed by his first-born son. In a polygamous family, the first wife held the most prestigious position among women.

The first-born son of the first wife was usually the main heir to his father, even if he happened to be younger than his half-brothers from his father's other wives. Daughters had no permanent position in Luhya families as they would eventually become other men's wives. They did not inherit property and were excluded from decision-making meetings within the family. Today, girls are allowed to inherit property, in accordance with Kenyan law.

Children are named after the clan's ancestors, after their grandparents, after events, or the weather. The paternal grandparents take precedence, so that the first-born son will usually be named after his paternal grandfather (Kuka or 'Guga' in Maragoli) while the first-born daughter will be named after her paternal grandmother ('Kukhu' or 'Guku' in Maragoli.)

Subsequent children may be named after maternal grandparents, after significant events, such as weather, seasons, etc. The name Wafula, for example, is given to a boy born during the rainy season (ifula). Wanjala is given to one born during famine (injala).

Traditionally, they practiced arranged marriages. The parents of a boy would approach the parents of a girl to ask for her hand in marriage. If the girl agreed, negotiations for dowry would begin. Typically, this would be 12 cattle and similar numbers of sheep or goats, to be paid by the groom's parents to the bride's family. Once the dowry was delivered, the girl was fetched by the groom's sisters to begin her new life as a wife.

Instances of eloping were and are still common. Young men would elope with willing girls, with negotiations for a dowry to be conducted later. In such cases, the young man would also pay a fine to the parents of the girl. In rare cases abductions were normal, but the young man had to pay a fine. As polygamy was allowed, a middle-age man would typically have two to three wives.

When a man got very old and handed over the running of his homestead to his sons, the sons would sometimes find a young woman for the old man to marry. Such girls were normally those who could not find men to marry them, usually because they had children out of wedlock. Wife inheritance was and is also practiced.

A widow would normally be inherited by her husband's brother or cousin. In some cases, the eldest son would inherit his father's widows (though not his own mother). Modern-day Luhyas do not practice some of the traditional customs as most have adopted a Christian way of life. Many Luhyas live in towns and cities for most of their lives and only return to settle in the rural areas after retirement or the death of parents there.

They had extensive customs surrounding death. There would be a great celebration at the home of the deceased, with mourning lasting up to forty days. If the deceased was a wealthy or influential man, a big tree would be uprooted and the deceased would be buried there. After the burial, another tree Mutoto, Mukhuyu or Mukumu would be planted. (This was a sacred tree and is found along most Luhya migration paths it could only be planted by a righteous lady mostly a virgin or a very old lady.)

Nowadays, mourning takes less time (about one week) and the celebrations are held at the time of burial. "Obukoko" and "Lisabo" are post-burial ceremonies held to complete mourning rites.

Animal sacrifices were traditionally practiced. There was great fear of the "Abalosi" or "Avaloji" (witches) and "Babini" (wizards). These were "night-runners" who prowled in the nude running from one house to another casting spells.

Sources: