The Nuer / Naath people are a Nilotic ethnic group concentrated in the Greater Upper Nile region of South Sudan and are from Ethiopia's Gambela Region. They speak the Nuer language, which belongs to the Nilotic language family. They are the second largest ethnic group in south Sudan and the second major ethnic group in Gambella. The Nuer people are pastoralists who herd cattle for a living. Their cattle serve as companions and define their lifestyle. The Nuer call themselves "Naath".

The Nuer people have historically been undercounted because of the semi-nomadic lifestyle. They also have a culture of counting only older members of the family. For example, the Nuer believe that counting the number of children one has could result in misfortune and prefer to report fewer children than they have. Their Ethiopian counterparts are the Horn peninsula's westernmost Horners.

The Nuer are believed to have separated - at a certain stage in the past - from the Dinka but in their latter development and migration assimilated many Dinka in their path.

‘Nei ti Naath’ which translates simply into ‘people’, is the second largest nationality in South Sudan.

In the beginning of the 19th century the Naath started to migrate and expand eastwards across the Nile and Zeraf rivers. This was done at the expense of, and more often than not, conquest and assimilation of their neighbours (most the Dinka, Anyuak and Maban).

The Naath now dominate large parts of Upper Nile extending from River Zeraf through Lou to Jikany areas on the River Baro and Pibor rivers. Nuer expansion pushed into western Ethiopia displacing the Anyuak more to the highlands.

District Major Section Sub Sections Clans

The Naath who number approximately 2 million are to be found as a federation of sections and clans in western (Bentiu), central (Pangak and Akobo) and in eastern (Nasir) Upper Nile. With the river Nile as the principal geographic dividing line, nei ti Naath Ciang (homeland Nuer) and 'nei ti Naath Door' (wilderness Nuer) form the first level federal division of the 'rool Naath' (the Nuer land).

In the 1930s the Nuer population was estimated to have been around 200,000 people. The British colonial government's census of 1952 put their number at 250,000. Sudan gained independence in 1956 but the country had already plunged into a north-south civil war starting in 1955, which continued through 1972. The first government census after the war indicated that the Nuer numbered nearly 300,000 in a country of 15 million at that time. That number was said to have gone up to 800,000 when the second round of civil war resumed in 1983. Over the last eighteen years of the war, at least a quarter of the two million estimated deaths are thought to have been Nuer and their current [Editor's note: ca. 2001] population is estimated as approximately 500,000 of Sudan's total estimated population of 26 million.

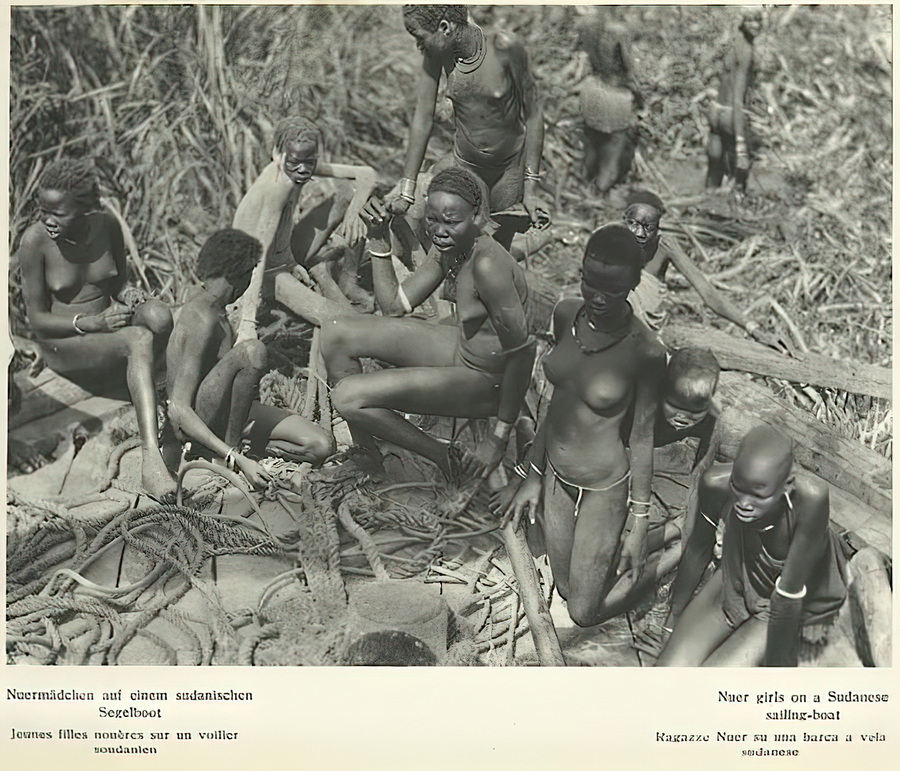

Most of Naath homeland is located in the swamp areas of Upper Nile. The influence of the environment on the lifestyle of the Naath is obvious. Naath are sedentary (although individual families domicile in solitary settlements) are agro-pastoralists balancing subsistence agriculture with cattle herding – Naath keep large herds, fishing and hunting.

The main crops are sorghum, maize (Jikany most probably adopted from the Anyuak) and tobacco. However, the Lou demonstrate yearly transhumance. The arid nature of their homeland in central Upper Nile dictates their dry season migration to the Sobat basin or to Zeraf basin precipitating feuds with Jikany (fishing rights), Gawaar and Dinka, respectively.

Western Nuer homeland is imbued with enormous deposits of petroleum. The discovery, development and exploitation of this natural resource is more of a curse to the Naath than a blessing. It is the cause of immense humanitarian disruption and destruction unprecedented in Naath history. Other natural resources potential include wildlife, fisheries, acacia senegaleise (gum arabica), and balantines aegyptiucm (laloob).

The Nuer people are said to have originally been a section of the Dinka people that migrated out of the Gezira south into a barren dry land that they called "Kwer Kwong", which was in southern Kordofan. Centuries of isolation and influence from Luo peoples caused them to be a distinct ethnic group from the Dinka. The Arrival of Bagarra Arabs and their subsequent slave raids in the late 1700s caused the Nuer to migrate en masse from southern Kordofan into what is now Bentiu. In around 1850, further slave raids as well as flooding and overpopulation caused them to migrate even further out of Bentiu and eastwards all the way into the western fringes of Ethiopia, Displacing and Absorbing many Dinka, Anyuak and Burun in the process.

The intrusion of the British in the 19th century greatly halted the Nuers aggressive territorial expansion against the Dinka and Anyuak.

There are different accounts of the origin of the conflict between the Nuer and the Dinka, South Sudan's two largest ethnic groups. Anthropologist Peter J. Newcomer suggests that the Nuer are actually Dinka. He argues that hundreds of years of population growth created expansion, which eventually led to raids and wars.

In 2006 the Nuer were the tribe that resisted disarmament most strongly; members of the Nuer White Army, a group of armed youths often autonomous from tribal elders' authority, refused to lay down their weapons, which led SPLA soldiers to confiscate Nuer cattle, destroying their economy. The White Army was finally put down in mid-2006, though a successor organisation self-styling itself as a White Army formed in 2011 to fight the Murle tribe (see 2011–2012 South Sudan tribal clashes), as well as the Dinka and UNMISS.

The Naath rose as a separate people (from the Dinka) in Bull area at the beginning of the 18th century under circumstances that continue to inform today their mutual prejudices and relations with the Jieng.

The myth, which has several variants, runs that both Naath and Jieng were sons of the same man, who had promised that he would give the cow to Jieng and its young calf to Naath. Jieng because of his cunning and intelligence deceived their father and took the calf instead of the cow therefore provokingl Naath’s perpetual contempt and disregard for the Jieng up to today.

The Nuer language is in the Nilotic branch of the Nilo-Saharan language family, a branch that includes Dinka, Luo, Shilluk, Anyuak and a number of other language groups. Linguistic similarities between these groups and the shared vocabulary indicate that there is a degree of shared origin or mutual influence between them.

Thok Naath – Nuer language is spoken all over the rool Naath. Being Nilotic, thok Naath is very close to the Jieng and Chollo languages. In fact, the Chollo and Jieng may have the same word 'cen' or 'cingo' (hand) the Naath calls it 'tet'. On the other hand the Naath and Chollo agree on 'wic' (head) while the Jieng call it 'nhom' and so on. The closeness of the language lays credence to the theory that the Naath, Jieng and Chollo have a common origin in time and space.

Nuer settlements have no particular order. Nuerland is right in the swamps of the upper Nile, and that means villages are grouped according to the lineage system into the few elevated parts. Because of their ecology Nuer engage in a near constant juggling of life between the cattle camps of the dry season and the villages that are located on the few mildly elevated parts of their territory where they grow millet. Their movement is dictated by tot and mai the two seasons that are determined by rain and drought respectively. Much of Nuerland gets flooded during the rainy season between April and October and this has caused shifting of villages from time to time. During the dry season between November and March, resources become limited and sending most members of the family to the cattle camp is the norm. Due to this seasonal migratory system, Nuer have been characterized as transhumance. Much of the civil war has been fought on the Nuer soil and that has had detrimental repercussions on Nuer village life. Whole villages were burnt and displaced and populations have constantly moved from one place to another over the last two decades. In their villages, Nuer build huts of round mud walls and conical grass roofs that are windowless and have small doors that force these long-legged people to crawl into their homes. Recent oil explorations and development have brought serious disasters to Nuerland and more villages have been burnt since 1998 to create a security buffer zone and make way for foreign oil companies that suspect Nuer hostility.

Nuer livelihood now on the upper Nile is based on a combination of, in the order of their importance, cattle herding, horticulture, fishing, and wild foods. Cattle are the Nuer's most cherished possession. They are essential food-supply as well as the most important social asset. It is therefore, hard to imagine discussing any aspect of Nuer's history and culture without reference to cattle. Cattle play a foremost part in ritual. Nuer institution, customs, and most of their social behavior directly concern their cattle. They are always talking about their animals, and a fuller understanding of their culture would require a look at the role of cattle in folklore, marriage, religious ceremonies, homicide, and relations with their neighbors. The Nuer say a cow is like a human being and should not be slaughtered solely for meat, except in sacrifice to God, spirits, and their ancestors. An ox can also be slaughtered to feed important guests as at marriage ceremonies. In recent times more Nuer have slaughtered their livestock due to severe famines that have afflicted South Sudan over the last two decades of the war. But in general they eat the meat of every animal when the beast dies.

Almost every cultural practice and social activity among the Nuer relate to livestock. The circulation of cattle between members of a lineage dictates such kin relations. Cattle and other types of livestock such as goats and sheep have a special position in religious ceremonies. Animals are sacrificed for treatment of sickness, as a way of prayer for rains, fertility, good crop yield, and to appease the ancestors. Cattle are not only of great economic and religious interest to Nuer, but they live in the closest possible association with them. Irrespective of their economic utility, cattle are an end in themselves, and the mere possession of them and living with them is a Nuer man's ultimate desire. More than anything else, they determine his daily actions, and because of their wide range of social and economic uses, cattle dominate a man's attention. Livestock is the currency in trading transactions.

Although Nuer economy is based on a combination of cattle herding, horticulture, and piscatorial activities, it is pastoral pursuits that take precedence in their lives because cattle do not only provide the daily nutrition, but are also of a general social value in all other aspects of their lives. Traditionally, when there was shortage of food and nowhere to barter, people relied on wild foods and fishing. To their economic activities, they have in recent times added trading as an important source of subsistence. Wild foods are also abundant during certain times of year throughout Nuerland. Recent famines, displacement, and loss of assets due to the war have further forced the Nuer to regard wild foods, trading and fishing as very important components of their economy. Besides grain and dried fish, the Nuer do not have non-perishable food items that can be stored for extended periods of time, and for this reason, their subsistence can best be described as a subsistence economy. The goal of economic activity is to satisfy immediate dietary needs rather than accumulate wealth. In fact, even when a household may harvest surplus grain, they convert it into cattle. So it is safe to suggest that cattle are the only economic item that is long lasting and can be inherited. The Nuer are fortunate in terms of agriculture. The soil is black cotton soil that maintains its fertility at all times. People may use slash and burn horticulture if soil becomes eroded, which is rare. Their main crops are millet (sorghum), maize, and vegetables. Nuer agriculture is typically a horticulture activity in the sense that they use rotation of crops and their tools are rudimentary ones that include the hoe. New tools were recently introduced by relief aid agencies to assist displaced persons reestablish their lives in displacement. The area of land that a Nuer household cultivates varies according the its labor force. On average a Nuer household grows two acres. When crops fail in one area due to either floods or droughts, grains can be purchased from areas of surplus within Nuerland or in the towns where Arab traders keep shops.

Barter existed in Nuerland before markets. A person who produced surplus food could exchange it for livestock. When the Nuer were introduced to such town items as sugar, salt, clothes, medicine, and soap, and their desire for them increased, it was very hard to acquire them since there was no paid labor within Nuerland and no other type of cash economy. The easiest and most obvious way for them to buy these goods was to sell livestock in the city. But selling cattle was something the Nuer had an aversion toward; it was considered a shameful act. It was not until the British colonial government imposed a poll tax and insisted on cash that the Nuer sold livestock. When Arab traders began to venture into Nuerland to sell a few of these items and later opened shops, grain became available in these Arab-owned shops. A few Nuer began to get involved in trading as well by selling old oxen in the city and then buying trade items, and sometimes returning to the city with the money to purchase more cows. Trading became another means to increase one's herd. However, in the 1970s when the first war ended and reconstruction began, the Nuer found opportunities for paid labor in the cities' construction projects. Much of the money made was to buy the basic supplies and cows.

Nuer produce a variety of functional arts including clay pots, mats, decorating gourds used as eating utensils, and basketry. Sewing papyrus into smooth mats is a particular industrial art that takes Nuer individuals a long time. Mats are the basic bedding.

Historically, trading was not an important aspect of Nuer economic activity until about a half century ago when Arab mobile traders went from village to village selling salt, cloths, beats, and medicine. These items were purchased with small livestock or chickens and when cash became available, women brewed beer that could be sold to buy these items. When northern traders realized that the South, including Nuerland, was a fertile business ground there was an influx of Arab goods and the markets grew. Nowadays, Nuer men and women have gotten involved in trading, but it is still largely a male preserve as it involves long distance travel to acquire the goods and the security situation being as it is, travel is limited to men. Goods get smuggled out of the North as well as from the neighboring countries of Kenya and Uganda. Over the last decade, international humanitarian relief has facilitated trade by providing cargo space aboard its trucks and planes.

Division of labor is not very different from that of the neighboring groups. In general, there are certain tasks that are regarded as for women and others for men, but there is a great deal of flexibility in this divide. Women's work tends to take place around the homestead or the village. It includes farming, food preparation, and care for the young and the very old. Men's work takes them farther away from home since much of it involves looking after cattle. In the field of food production, ideally both men and women plant crops; women weed, men harvest, women thresh the grain, store and pound it into flour, and prepare the daily meals. Men graze the livestock far afield. Women, girls and uninitiated boys milk them. Construction of houses is generally shared. Men build the walls, cut and transport timber, and put up the frame, and both genders can thatch the grass roofs. The only areas of rigid sexual division of labor are milking the cows and cooking. Initiated men should never, under ordinary circumstances, cook or milk the cows.

Like in all of South Sudan, Nuer land is under communal ownership. Individuals can take, tame, and use as much land as their labor capacity could allow. It is this continual use that entitles people to land. If they move away, it can be taken over by others. When a household moves somewhere else, they may demand payment from the next occupants as remuneration for the labor expended in taming it and for any dwelling structures that may still be useable. The only piece of land that is contested is the grazing plains. Even here, the actual grasslands are not restricted to any group, but the elevated camps where the people reside are designated according to lineage.

The Nuer are patrilineal but people are considered to be related equally to other kin through both the mother's and the father's side. For this reason, Nuer descent could be best described as cognatic. Like most human societies, the Nuer consider kinship as the most important basis of social organization. People establish whether or not they are related by their clan names. Members of a clan share a totem and believe in descent from that totem. It is also on the basis of clan membership that strong marriage or sexual prohibitions are built and enforced.

To a Nuer individual, his parents and siblings are not considered mar (blood relatives) kin. He doesn't refer to them as kin. To him they are considered gol which is far more intimate and significant. There are kinship categories in the Nuer society. Those categories depend on the payment to them. There is a balance between the mother and father's side that is acknowledged through particular formal occasions such as marriage.

Nuer girls usually marry at 17 or 18. If a young girl gets engaged at an early age, the wedding and consummation ceremonies are essentially delayed. Women generally give birth to their first children when they are mature enough to bear them. As long as a girl marries a man with cattle, she is able to freely choose her husband, however her parents may choose a spouse for her.

Kinship roles

Kinship among the Nuer is very important to them, they refer to their blood relatives as ``gol”. Kinship within the Nuer is formed off of one's neighbors or their entire culture. During E.E.Evans-Pritchard's ethnographic observation, he described the role of kinship as: “Kinship obligations include caring for the children of one’s kin and neighbors. He also observed that,"The network of kinship ties which links members of local communities is brought about by the operation of exogamous rules, often stated in terms of cattle." This is never thought to be the sole responsibility of the child's parents." Cattle are judged by how much milk they can produce which is a necessity in their culture. If possible they create the excess of milk into cheese. But if a family’s herd cannot produce the amount of milk a family needs then they turn to other around them to give them what they need. It’s seen as their responsibility to step in and help the family since it’s not really their fault on how much their cattle can produce. The entire Nuer society is basically watching after each other, for example, as Evans-Pritchard noted that,“When one household has a surplus, it is shared with neighbors. Amassing wealth is not an aim. Although a man who owns a large herd of cattle may be envied, his possession of numerous animals does not garner him any special privilege or treatment.” In this tribe there is no special treatment for how one is treated because of their abundance in cattle. Just because one might have more cattle than another doesn't mean they have a higher prestige. If one might have more than enough to provide for themselves then they also provide that to other kin that are in need, as it is a part of their role in kinship.

Children have to learn the kinship terminology at a very young age and have to apply it strictly in their daily interaction with adult relatives. It is the means by which individuals express their respect for one another. Those that do not share an age set cannot address one another by their first names. Kinship terminology is intended to maintain the descent group; and descent functions in organizing domestic life, enculturating the children, allowing the transfer of property and ritual roles. It also settles disputes. The responsibilities, obligations, and rights derived from descent membership and expressed through the terminology extends far and wide. It is bifurcate collateral terminology.

Once married, the couple may reside with the man's family for some time before moving out to establish their own home. The couple is free to live in a place of their choice but residence with the man's family is most preferred.

Children are cared for by both parents, by grandparents, and by elder siblings or any other relatives willing to do so. Nuer boys and girls are socialized differently. Boys are generally concerned with cattle and with serving the adults at the cattle camp. Because of the gender division of labor girls are expected to identify more with their mothers who instill in them the women's roles. Boys usually identify with their fathers who engage them in manly activities and teach them their responsibilities for work and war.

Nuer organize around clans and lineages, the latter being a smaller segment of the former. The degree to which people relate to one another is based on where they fall from one another on the kinship tree. The narrower the gap in structural distance the more likely the relatives will share a village. Those members of a lineage who live in an area associated with it see themselves as a residential group, and the value, or concept, of lineage therefore functions through the political system. A clan has a headman. Several headmen are appointed as government sub-chiefs, who serve under an executive chief. Nuer is a segementary society. Group size can change according to political circumstances. For example, many clans may form a phratry and reside together if there is need for collective defense, and simply break up when that need no longer exists.

The Nuer are divided into a number of sub-groups, which have no common organization or central administration. They may be politically described as tribal sections. Some live in the homeland to the west of the Nile and can be distinguished from those that have migrated to the east of it. Therefore, speaking of their political organization, it is safe to distinguish between Western Nuer and Eastern Nuer. The Eastern Nuer may be further divided into those tribal sections living near the Zaraf River and those living to the north and south of the Sobat River. In each of these groups, there are headmen, sub-chiefs, executive chiefs and paramount chiefs. These are all politicized positions that only emerged with the rise of the nation. Prior to this, Nuer political and administrative structure relied on community elders who enforced norms and regulations through a combination of respect and fear.

Within the Nuer, homicide is common and is usually related to cattle. Nuer say that more people have died for the sake of a cow than for any other cause. Acts of homicide can be immediately avenged or held as blood-feuds until such time when the two sides finally square even, and the mechanism to deter homicide and revenge has been the imposition of blood wealth, which is payable in cattle. The norm has been 30 cows paid to the family of the slain person. It can therefore, be said that because cattle are a source of turmoil, a threat of one's cattle being taken away in punishment induces prudence in the relations between people.

The relationship with the Dinka, as far as history and tradition go back, has been based on a cycle of war and reconciliation, all because of cattle rustling or thefts. They even have a myth in which the two groups are represented as two sons of God who promised his old cow to Dinka and its calf to Nuer. One night Dinka came and took the cow from God by imitating the voice of Nuer. When God realized that he had been cheated, he was angry and charged Nuer to avenge this by endlessly raiding Dinka's cattle. Now, Nuer always raid for cattle and seize them openly by force of arms.

Although large numbers of Nuer have converted to Christianity over the last two decades, the majority of them remain followers of traditional religions whose central theme is the worship of a high god through the totem, ancestral spirits, and a number of deities. The high god is called kuoth and he is the source of life followed by a host of earth deities. Nuer religious practice involves sacrifices of animals at designated times of year such as beginning of the rainy season, blessing of harvest, and end of year ceremonies. At these prayer gatherings, the religious practitioners call for peace, good human and animal health and fertility of both. Ancestral spirits are presumed to be able to increase productivity of the land, increase in cattle and safety for all. They are thought to watch over the living, to reward good behavior and punish wrongdoing. They function as mediators between the dead and the living. There are times when gods need to be appeased, especially when angered by human behavior, and rituals are performed for these occasions. All these practices were a source of misunderstanding between the Nuer and the Christian missionaries. When they first arrived in Nuerland, the missionaries believed that the Nuer were worshiping idols. But from the Nuer point of view, praying at a totem did not represent praying to the totem itself but rather as a place of worship no more paganistic than going to a church or mosque. However, due to the religious conflict between north and south of Sudan, Christianity has grown steadily among the Nuer in the last twenty years, and Nuer Christians are currently estimated at 30%.

The central figure in Nuer religious practice is the leopard-skin-chief, but there have been numerous prophets that people have believed in, the highest of whom has been Ngun Deng. He rose in Lou Nuer and his pyramid remains the highest and most amazing religious monument in Nuerland to date. The practices of traditional religious leaders in Nuerland have been regarded as complimented by Christianity and there is no conflict between Christianity and Nuer religion, whereas the Nuer believe that there is contradiction between their traditional beliefs and Islam.

The Nuer (Naath) people are an extremely religious people whose beliefs can be summarized by the word Kuoth (God). “Kuoth (God) is an all-encompassing God associated with the sky, but is always present in all things, living and dead, and is also associated with many spirits; and the spirit form of Nuer tradition.” In the Nuer culture, Kuoth (God) “supplies explanation for phenomena which cannot be explained in everyday life.” Because of the fact that it is accepted without question, the Nuer have difficulty of explaining Kuoth (God) because of “its abstract nature and the fact that it’s used to generalize the spirits of who possesses people.” Kuoth (God) is always given the role of creator, and is said to be the origin of the ancestors.

The Nuer people, however, were traditionally sophisticated enough to adhere to the concepts of “aliveness” which include the notion of a soul or spirits residing in the object. They treat the objects they consider animate as if these things had a life, feeling, and a will of their own, but “did not make a distinction between the body of an object and soul that could enter or leave it.” The reverence that Nuer people in Sudan grant to deceased relatives is based on believing that in dying, they have become powerful spiritual being or “even admittedly less frequently to have attained the status of gods.” This is usually based on the belief that ancestors are active members of society, and still interested in the affairs of their living relatives.

The cult of ancestors is certainly common although not universal and has been particularly well documented in many African societies. In general, “ancestors are believed to wield a greater authority, having special powers to influence the course of events or to control the well-being of their living relatives.” They are often considered as the “intermediaries between the supreme God, the people and they can communicate with the living through dreams and by possession.” The attitude toward them is one of mixed tear and reverence and If neglect, the ancestors in heaven may cause diseases, drought, famine and misfortunes. Instantly in the Nuer societies, “propitiation, supplication, prayer and sacrifice” are the various ways in which the living can communicate with their ancestors. Ancestors worship is a strong indication of the value placed on the household, and of the strong ties that exist between the past and the present. “The beliefs and practices connected with the cult help to integrate the family to sanction the traditional political structure, and encourage respects for the living elders.” The Naath prophets arose and left their mark on the Naath nation. Ngundeng, who rose in Lou, remains the most revered. Younger and less important prophets have arose with the last one who left an impact being wud Nyang (1991-1993).

The Nuer engage in elaborate ceremonies that are social and religious in nature. Health ceremonies are usually expansive. Dance and singing are crucial aspects of Nuer entertainment. The Nuer are very expressive and such dances are the ultimate young people's opportunity to interact and court. Although the Nuer do not conduct elaborate burial ceremonies, the death of a spiritual leader is always marked by a huge celebration whereby cattle camps gather and young men engage in mock battles, sing to their favored oxen, and feast. In the past a well-known spiritual leader might be buried alive as a way to prevent his soul from taking the good health of the whole society with him. When he was thought to be dying, cattle camps were moved to his house and celebrations went on for days, during which time he is laid in the grave until the time it is deemed appropriate to bury him.

Although potent and biochemical medicine have been introduced into Nuerland for quite some time and Nuer believe in their efficacy, traditional therapeutic medicine is still highly regarded. It is sometimes the only medical system available as the war has destroyed whatever health units there were. For this reason Nuer can be seen as engaging in multiple medical practices The therapeutic techniques that are in use among the Nuer include various kinds of surgery, dispensing medicinal plants, and bone setting. These are all learnable techniques and can be passed down between generations. But other practitioners whose skills are "god given" practice healing methods throughout Nuerland. They include diviners who are believed to diagnose by means of communicating with the supernatural world. They are widely believed in, but the rising number of people who understand the concept of germs, viruses, and parasites and who understand the way biomedicine works have started to challenge them.

Naath arts, music and literature like in most unwritten culture are orally transmitted over generations in songs, stories and folktales. The Naath are rich is songs, and folktales. Naath articles of arts and music include 'thom' and 'bul', which are similar to those of other Nilotics. Their articles for self-defence include different types of ket (stick) mut (spear). A man carries goh or gok (charcoal and tobacco bags) and a 'thiop kom'.

The different Naath sections have evolved their different dances: 'buul' performed during the early afternoon especially for marriages; dom-piny (a hole in the ground covered with a skin) is performed during the night where wut and nyal court themselves. Of the most important handcraft the Naath have developed is the dieny (basket for carrying everything including children when on a long journey).

Naath cultural initiatives that have now become Sudanese national cultural heritage is the Mound of Ngundeng at wic Deang in Lou.

Normally when a person is alive, her soul is thought to roam about during sleep. The soul must return before the person wakes up. This is how dreams are believed to happen. So dreams are actually things the soul has encountered while roaming the world. Death means that the soul has failed to come back before the person woke up, and so realizing that it is too late to rejoin the body, it goes to join the souls of the relatives who have died before to live together with them.

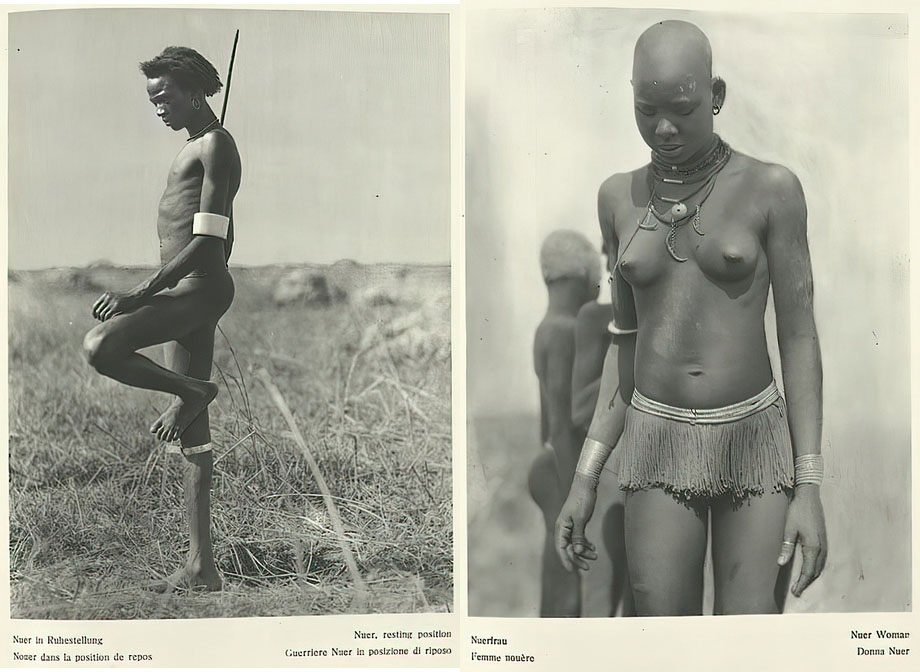

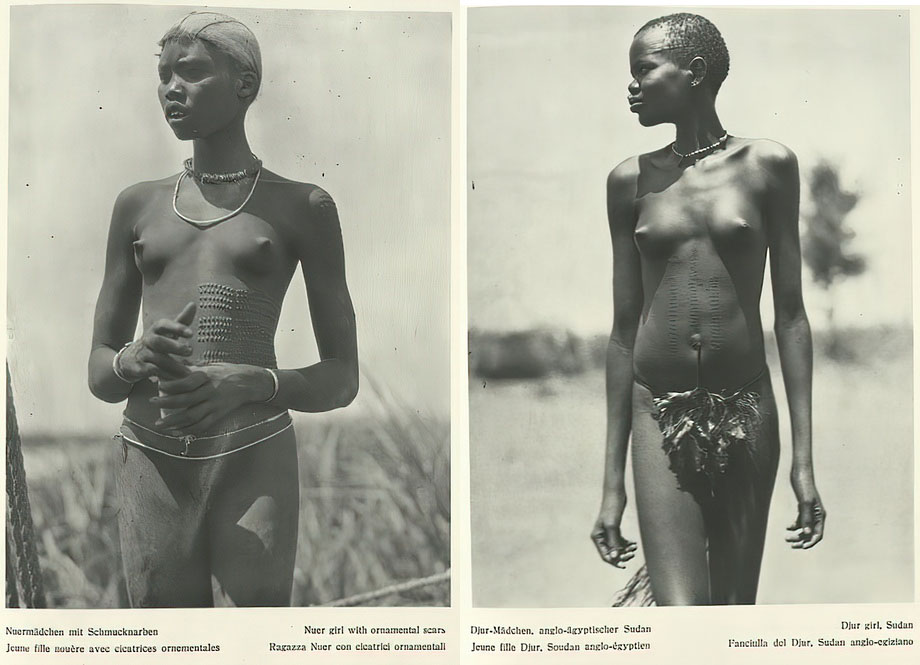

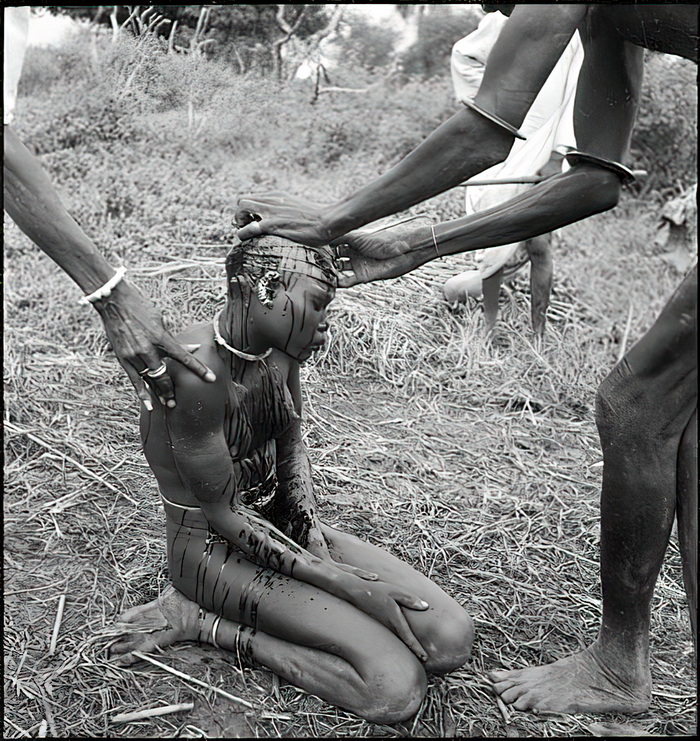

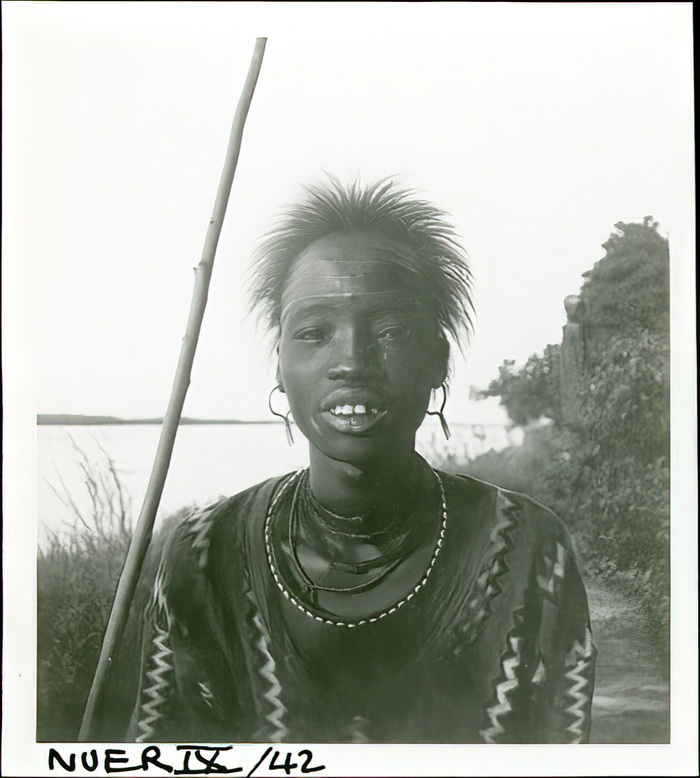

Naath remove the 4 incisors and 4 lower canines as a sign of maturity for 'dholni' (children) of both sexes. However, initiation into 'wut' (adulthood) which is usually cutting 5 to 6 parallel lines across the forehead is undertaken among dhol (boys) of the same age, which like in other Nilotic groups form them into a 'ric' (age set).

The nyal and wut are now ready for marriage, which is prohibited among blood relatives or kins. Marriage is settled in cattle, whose numbers vary from section to the other but ranges from between 35 to 45 on average.

Nuer life revolves around cattle, which has made them pastoralist, but they are known to sometimes resort to horticulture as well, especially when their cattle are threatened by disease. Due to seasonal harsh weather, the Nuer move around to ensure that their livelihood is safe. They tend to travel when heavy seasons of rainfall come to protect the cattle from hoof disease, and when resources for the cattle are scarce. British anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard wrote, “They depend on the herds for their very existence...Cattle are the thread that runs through Nuer institutions, language, rites of passage, politics, economy, and allegiances.“

The Nuer are able to structure their entire culture around cattle and still have what they need. Before development the Nuer used every single piece of cattle to their advantage. According to Evans-Pritchard, cattle helped evolve the Nuer culture into what it is today. They shaped the Nuer's daily duties, as they dedicate themselves to protecting the cattle. For example, each month they blow air into their cattle's rectums to relieve or prevent constipation. Cattle are no good to the Nuer if constipated because they are restricted from producing primary resources that families need to survive. Evans-Pritchard wrote, "The importance of cattle in Nuer life and thought is further exemplified in personal names." They form their children's names from biological features of the cattle.

Evans-Pritchard wrote, "I have already indicated that this obsession—for such it seems to an outsider is due not only to the great economic value of cattle but also to the fact that they are links in numerous social relationships." All their raw materials come from cattle, including for drums, rugs, clothing, spears, shields, containers, and leather goods. Even daily essentials like toothpaste and mouthwash are created from the cattle's dung and urine. The dung is chopped into pieces and left out to harden, then used for containers, toothpaste, or even to protect the cattle themselves by burning it to produce more smoke, keeping insects away to prevent disease.

The Nuer people never eat cattle just because they want to. Cattle are very sacred to them, therefore when they do eat cattle they honor its ghost. They typically just eat the cattle that is up in age or dying because of sickness. But even if they do so, they all gather together performing rituals, dances or songs before and after they slaughter the cattle. Never do they just kill cattle for the fun of it. “Never do Nuer slaughter animals solely because the desire to eat meat. There is the danger of the ox’s spirit visiting a curse on any individual who would slaughter it without ritual intent, aiming only to use it for food. Any animal that dies of natural causes is eaten.” Many times it may not even just be cattle that they consume, it could be any animal they have scavenged upon that has died because of natural causes. There are a few other food sources that are available for the Nuer to consume. The Nuer diet primarily consists of fish and millet. “Their staple crop is millet." Millet is formally consumed as porridge or beer. The Nuer turn to this staple product in seasons of rainfall when they move their cattle up to higher ground. They might also turn to millet when the cattle are performing well enough to support their family.

Among the Nuer, marriage and the family are the most fundamental institutions and are everyone's goal. Polygynous marriages are common among the Nuer. Marriages of members of any local group are usually the best way of creating innumerable links through women between persons of many different communities. This makes maternal and affinal ties in kinship reconfigurations an essential aspect of Nuer kinship as exogamous rules are strongly enforced on both sides. A man may not marry any close cognate. Nuer consider that if a relationship can be traced between a man and a woman through either their mother or father, however distant, marriage should not take place between them. Courtship is open among those who have established non-existence of any consanguineal relationship. Courtship (always initiated by men) is the preferred method of finding potential mates. After the male initiation ceremony, a young man takes on the full privileges and obligations of manhood in work, war, and play. Courtship and cattle become a young man's major interests, and he takes every opportunity to flirt. Marriage is in the sequence of birth and order of kinsmen. When it is his turn to get married, a Nuer man is asked by his family to identify which, among the girls he has courted, he loves the most. Once the family has reached an agreement, the elders of his family make a visit to the woman's family to announce their intention and to discuss the number of cattle to be paid in bride-wealth. The union of marriage is brought about by payment of cattle and every phase of the ritual is marked by the transfer or slaughter of cattle. Some Nuer couples may decide to elope and then the question of bride-wealth is settled later, but this method is risky as the two families could end up in a bloody battle.

Nuer marriages are quite stable, and grounds for divorce are limited; a woman's failure to conceive is one of them. Since marriages involve exchange of property, which is often contributed by different members of the extended family, individuals do not have total freedom to terminate marriages. Decisions regarding divorce are usually subjected to the scrutiny of both sides before they are final as the groom's family has invested materially in the marriage, and the bride's family does not want to loose the bride-wealth received.

Marriage for the Nuer is made up of payment of bridewealth and by the performance of certain ceremonial rites. These two aspects are necessary and indeed reinforce each other. The chief ceremonies in Nuer marriages include the betrothal (larcieng), the wedding(ngut) and the consummation (mut). In thsee procedures, we shall see the significant use of cattle in Nuer marriages.

The negotiations of bridewealth, or cattle talk (riet ghok) starts when the boy comes to consult the girl’s and ask kins for approval. After several cattle discussions and the girl’s people are satisfied, they would tell the bridegroom that he can bring the ghok lipa, the cattle of betrothal, on a certain day. During the betrothal ceremony three to ten heads of cattle are transferred to the bride’s family. At this phase, marriage is provisionally agreed upon both families. The celebration would be usually be attended by neighbours. The dance in weddings attract crowds to come, although the union do not directly concern them. Families and kin of the bride and groom are more involved in prolonged discussions about bridewealth, sacrifices and other rites.

The wedding ceremony (ngut) takes place some weeks later, during the windy season, and meanwhile there are further discussions about bridewealth not only in the home of her bride’s father but also in the home of her senior maternal uncle(father’s brother-in-law), who is also responsible for the negotiations. In the meantime, bridegroom and girl is considered man and wife, and he is respected as son-in-law. Occasionally visits the girl with his friends, but they are carefully observed by bride’s family.

The final cattle talk happens during the ngut. The wedding also consists of calling of the ghosts of ancestors, the wedding dance and sacrifice of the cattle. There would be chantings to invoke the ghosts of ancestors to look upon the cattle of the bridewealth. This is to make the ghosts witnesses of the union. In the evening or the following morning, a wedding ox provided by the bride’s father is sacrificed and distributed. This sacrifice is important to ward off evil and contamination, according to Nuer’s religious beliefs.

The consummation (mut) concludes the marriage. Before the couple is allowed to consummate, half of the bridewealth have to be transferred.This ceremony makes the couple husband and wife. After which, the husband can claim compensation if adultery happens, while the bride is prevented form going to evening dances. Important rites in this ceremony include the sacrifice of an ox, lustration and shaving of the bride’s head. Because the union is seen complete only after the birth of the first child, the wife would only be brought to her husband’s home after that, where she would be accepted as kin. Again this feature is important in Nuer marriage because infertility could cause the marriage to be dissolved and so the wife is pressured to have a child within one to two years (Moore,1998). The payment of bridewealth is to be completed before the woman moves into her husband's clan.

Bridewealth makes up an important aspect in Nuer marriages. Bridewealth serves several functions. It is basically an exchange whereby the girl is transferred to the male’s lineage and her family receives the cattle. It also means that children born out of that union belongs to the husband’s descent. In addition, bridewealth is a way to develop relationship between two families. It is different from dowry such that bridewealth is not given for the bride alone but also distributed among her kins (Goody, 1973). Because marriage is a long process for the Nuer, bridewealth payments can be seen as a way to develop social relations among people with no kinship ties(i.e. between families of the bride and bridegroom). Each payment gives stability to the union and security to both parties.

The Nuer has certain marriage prohibitions that revolve around the matters of kinship. A man and woman who stand on a relationship based on kin is hence forbidden to have sex or marry. If marriage takes place, it would be considered incest, or rual. Rual refers to both incest and misfortune brought about it, shaped by their religious beliefs. Syphilis or other diseases, drowning, or any form of violent deaths are seen as a consequence or retribution followed by incest. Some misfortunes could be avoided through cattle sacrifices.

Nuers have to follow the rule of exogamy: a man cannot marry a woman of the same clan and the same lineage. This means, a man and woman who are considered close cognate are also not allowed to marry. As long as a relationship cam be traced between a man and woman through either father or mother, up to six generations, marriage is not allowed to happen (Evans-Pritchard, 1951). Further, when a Dinka boy is adopted by a Nuer, he used be regarded as part of the clan, and normally would not be allowed to marry a girl in the clan he is adopted. A man may not also be allowed to take a woman that is kin to the wife, like her sister or any of those in her clan. Because a man and woman is only fully married when the woman has a child and comes to live with her husband’s people, this means that the relation is tied through the child. The sister is also considered to be the mother of the child. Besides that, a man may not marry to the daughter of his “age mate”, a member of his age set. This is because age-mates shed blood together during their initiation process and gives them a kind of kinship. The daughter one’s age-mate is also one’s daughter, and hence it would be considered incest.

One alternative marriage type is same-sex marriage. Women in Nuer culture can marry each other, with one being the ‘father’ of the children of the ‘wife’. The ‘father’ is referred to the ‘pater’. A third person, the ‘genitor’, is required to impregnate the wife. He could be a friend, neighbor or kinsman of the pater, and would help around in the home for tasks which are deemed unfit for women as well. For the marriage to become official, the 'pater' has to pay a bridewealth to the wife, as would happen if a man were to marry a woman.

Additionally, the pater would also receive bridewealth if any of her daughters were to marry. While this was not uncommon, the underlying motivation is still to carry on the family name. A woman who marries as a 'pater' is usually barren, and for this reason is regarded like a man. In addition, because a barren woman usually practices as a magician or diviner, she acquires more cattle and hence is rich and could have several wives (Evans-Pritchard, 1951).

Another alternative marriage arrangement is ghost marriage. A woman would be chosen to marry a family member of the dead man, and the offspring of these two would be thought of as belonging to the deceased. This lies in the belief that a man who died without male heirs would leave behind an angry spirit to trouble the family. The woman marries to his name so that the children would carry his line. The deceased is the legal husband of the woman whose name is used in paying for bridewealth. The main idea here is the continuity of the lineage.

Another type of union mentioned by Evans-Pritchard is levirate. For the Nuer, once married, the bond between them stays even after death. While polygyny is practiced in the Nuer society, a woman is expected to stay loyal to her husband, where relation with other man is seen as adultery. Hence if one’s husband died, the woman is not allowed to remarry because she is still the wife of her dead husband. Brother of the deceased would then step in as a substitute for the dead man. Because married women traditionally do not have significant wealth, this way she would be able to keep her wealth and power, though there is no living husband (O'Neil, 2009). She is seen as a widow who takes care of her husband’s wealth and children.

The alternative marriage arrangements for the Nuers are shaped by the patrilineal nature of the society. Because men tend to have much more wealth than women, they have the means to have more wives and even pass down their wealth to future generation even he is not married when he is alive.

Having a family is one of the ultimate goals for traditional Nuer youths. The idea of marriage has been ingrained even through childhood. Adults are open about sexual life with their children, and children familiarise themselves with marriage through role-playing of marriage ceremonies, conducting bridewealth negotiations and pretending having a conjugal life. Carrying out domestic work also helps to reinforce the idea of family and commitment. Boys are initiated around the age of 16, after which they would go to dances to woo girls. Girls in their 12 or 13 would begin to have relations with initiated boys.

Dances serve as an important medium where couples meet and court after that. It allows youths from different clans and villages to meet each other. During the dances the men would charm the girls with their fine dancing and “display of spearmanship and duelling with the club”(Evans-Pritchard, 1951).

Sexual activities among Nuer youths are shaped by cultural values. As such, even though they could have multiple partners in the course of their youth, the final goal of their sex life is ultimately marriage, for the chief ambition of a youth is to have a home of his own. Hence, a girl would tend not to have sex with a boy who do not have the intention to marry her. Although a Nuer youth usually has the freedom to choose his or her own mate, parents’ approval is still important, and this depends on whether the boy has sufficient cattle for bridewealth.

As we can see, pre-marital sex makes up not only an important aspect in the life for the nuer, but also an important step to marriage. For the Nuer, sexual reproduction is indeed a precursor to marriage. The main feature to describe Nuer’s marriage is that the union between a man and a woman is only confirmed by the birth of the couple’s child. Only then their relationship would be legitimate, and the husband would be accepted by his wife’s kins as one of themselves. This is because it is then clear that he is the father of their daughter’s child and through that child there is a kinship between them (Evans-Pritchard,1951).

The Nuer receive facial markings (called gaar) as part of their initiation into adulthood. The pattern of Nuer scarification varies within specific subgroups. The most common initiation pattern among males consists of six parallel horizontal lines which are cut across the forehead with a razor, often with a dip in the lines above the nose. Dotted patterns are also common (especially among the Bul Nuer and among females).

Some Nuer have begun practicing circumcision after being assimilated or partially assimilated in other ethnic groups. The Nuer are not historically known to circumcise, but sometimes circumcise people who have engaged in incest.

Typical foods eaten by the Nuer tribe include beef, goat, cow's milk, mangos, and sorghum in one of three forms: "ko̱p" finely ground, handled until balled and boiled, "walwal" ground, lightly balled and boiled to a solid porridge, and injera / Yɔtyɔt, a large, pancake-like yeast-risen flatbread.

In the early 1990s about 25,000 African refugees were resettled in the United States throughout different locations such as South Dakota, Tennessee and Minnesota. In particular, 4,288 refugees from Sudan were resettled among 36 different states between 1990 and 1997 with the highest number in Texas at 17 percent of the refugee population from Sudan.

The Nuer refugees in the United States and those in Africa continue to observe their social obligations to one another. They use different means ranging from letters to new technologically advanced communication methods in order to stay connected to their families in Africa. Nuer in the United States provide assistance for family members’ paperwork to help their migration process to the United States. Furthermore, Nuer in the United States observe family obligations by sending money for those still in Africa.

With strong and powerful neighbours the Naath can maintain peace and harmony with their neighbours. The Naath have cordial relations with the Tet (Chollo) from whom they have intermarried with. Naath cherish independence and freedom including freedom to invade others and take over their property, which makes for uneasy and sometimes violent relations with Dinka and Anyuak. They abhor anything that insults their sense of homeland for instance at their initial contacts with the Arabs and Turks, the Naath took offence of Muslim prayers in their land.

Oil exploration and drilling began in 1975 and 1976 by companies such as Chevron. In 1979 the first oil production took place in the southern regions of Darfur. In the early 1980s when the North-South war was happening, Chevron was interested in the reserves in the south. In 1984 guerrillas of SPLA (Sudan People's Liberation Army) attacked the drilling site of the north at Bentiu. In return, Chevron cleared Nuer and Dinka people in the oil fields area to ensure security for their operations.

The Nuer-Dinka struggle in oil fields continued in late 1990s into the early 2000s. The struggle for oil production was not only manifested in North-South fight, but also in Nuer-Dinka and many internal conflicts among Nuer.

As part of Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), 50 percent of net revenues of southern oil fields were given to the government of southern Sudan as a solution to one of the sources of decades of civil conflict.

Modernity, monetary economy, war, discovery of oil have had profound impact on the Naath traditional ways. Increased violence has resulted in massive displacements and movements of people that out of necessity have resulted in some positive change in attitudes and perceptions.

There is a large Naath Diaspora in North America and Australia. Like the seasonal labour migration to northern Sudan, this could be temporary because most of the Naath in the Diaspora are still intimately attached to their home and are likely to return now that peace is back in South Sudan.

Sources: